Isabela Cristina Coelho da Cunha e Castro1*, Ariane Furbringer2, Amanda Eduarda Nitchai2, Flavia Turmena Baggio2, Gabriela Dal Piva2, Glauco Araujo de Oliveira2, Júlia Casanova Vinhaga2, Leticia Woinarovicz2, Lucas Souza Schaedler2

1Professor of Departament of Surgical Clinic at Medical School, University of Vale do Itajaí

2Student at Medical School, University of Vale do Itajaí

*Corresponding Author: Isabela Cristina Coelho da Cunha e Castro, Professor at Medical School, University of Vale do Itajaí.

Introduction

Urachal anomalies are rare pathologies originating from the urachus, an embryological tubular structure located between the peritoneum and the transversalis fascia, which, around the 4th to 5th gestational month, undergoes obliteration and transforms into a fibrotic tubular structure forming the median umbilical ligament [15].

Among urachal abnormalities, four categories have been described: urachal sinus, urachal cyst, patent urachus, and urachal diverticulum [12]. Epidemiologically, the exact prevalence remains undefined; however, studies suggest that it is more common than previously thought, with a prevalence of approximately 1 in 600 children undergoing abdominal ultrasonography [8] and around 2% in adults [2].

In adults, the most frequent anomaly is the urachal cyst, followed by urachal sinus and urachal diverticulum. When symptomatic, the clinical presentation can vary, including abdominal pain associated with palpable masses in cases of infection [10], as well as dysuria, umbilical discharge, or even urinary leakage through the umbilicus [16].

More rarely, urachal anomalies can progress with complications such as fistulas to adjacent viscera, including uracho-colonic and uracho- enteric fistulas. [5, 12, 21].

Despite the absence of established protocols or guidelines defining a consensus on definitive treatment, urachal remnants can be managed conservatively or surgically, depending on the clinical presentation and the surgeon's preference. In adults, surgical management is generally recommended [7, 11, 20].

Due to its rarity in the literature, this article describes a case of a uracho-sigmoid-cutaneous fistula in an adult patient who was diagnosed and surgically treated at a Brazilian hospital.

Clinical Case

A 44-year-old male patient with a history of hypertension presented to the emergency department complaining of abdominal pain and discharge through the umbilical scar for the past 15 days, with no previous similar episodes. He denied fever, abdominal distension, or gastrointestinal alterations. On physical examination, he was in good general condition, afebrile, and showed no signs of sepsis. The abdomen exhibited hyperemia in the mesogastric region, with tenderness upon palpation in the periumbilical and hypogastric areas. The umbilical scar showed no active discharge. No abnormalities were detected in other systems.

Laboratory tests, including leukogram, electrolytes, renal function, C- reactive protein (CRP), and urinalysis, were within normal limits. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed a 2.5 cm umbilical hernia containing adipose tissue, associated with a tubular structure extending to the bladder, with thickened walls, surrounding fat stranding and gas content, suggestive of persistent urachus with associated infection. The urinary bladder was well distended, with smooth contours and homogeneous content.

The patient was diagnosed with an infected urachal cyst, discharged from the emergency department with a prescription for antibiotics and a follow-up appointment in the urology outpatient clinic upon completion of treatment was scheduled. At follow-up, he showed improvement in the infectious condition and a reduction in purulent discharge from the umbilical scar. He was subsequently referred for elective surgery.

One year later, while still awaiting elective surgery through the public healthcare system, the patient experienced daily leakage of gas and fecal discharge through the umbilical scar, with no other systemic abnormalities. He sought hospital care again and underwent a new abdominal CT scan, which reported: "Umbilical hernia with persistent urachus, containing interspersed gas and in close contact with a sigmoid loop, with no defined cleavage plane between the structures." Laboratory tests, including complete blood count, C- reactive protein (CRP), and urinalysis, remained within normal limits.

A diagnosis of a uracho-sigmoid-cutaneous fistula was established (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Abdominal computed tomography with intravenous contrast. A) Axial view showing a fistula between the urachus and the sigmoid colon (arrow); B) Longitudinal view demonstrating urachal persistence (arrows).

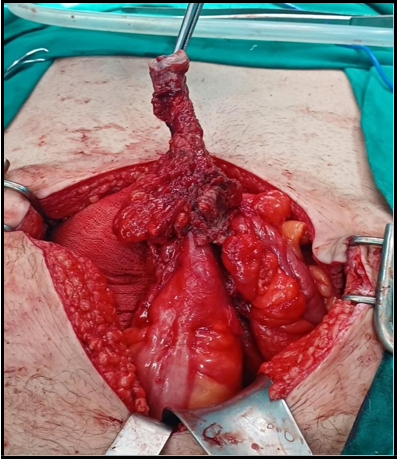

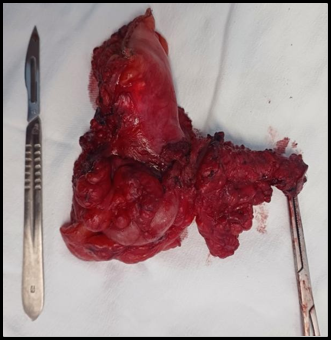

The patient underwent a new 7-day course of antibiotic therapy, followed by a retossigmoidectomy with en bloc resection by laparotomy. The middle third of the sigmoid colon was resected, including the fistulous tract and the urachus, with bladder suturing for hemostasis and primary colonic anastomosis, without complications (Pictures 1, 2, and 3). No communication with the bladder lumen was identified.

Picture 1: Appearance of the umbilical scar with a fistulous opening.

Picture 2. Intraoperative view showing the resection of the patent urachal tract containing the fistula en bloc with the sigmoid colon.

Picture 3. Surgical specimen of the en bloc resection of the urachus-sigmoid-cutaneous fistula.

The postoperative progression was satisfactory, with hospital discharge on the seventh day, follow-up at 14 days for suture removal, and a late follow-up at 60 days postoperatively, with no complications (Picture 4). The histopathological examination of the surgical specimen showed “Acute and chronic inflammatory process, fistulous, between the sigmoid colon wall and the urachus, with extensive areas of granulation tissue up to the adherent skin; the colonic segment exhibits a cystic area with mucinous content, without apparent epithelial lining; absence of malignancy.”

Picture 4: Abdominal appearance on the 14th day postoperatively.

Discussion

Complications of urachal anomalies are rare, and there are only 10 reported cases of urachal fistulas involving the intestine in the literature. Among the described cases, only two are of the urachus- sigmoid-cutaneous fistula type, the first reported in 2009 as a result of an infected urachal cyst [1], and the most recent report published in 2025, treated by laparoscopic surgery [19].

Authors suggest that inflammatory or infectious processes of urachal remnants [1, 10, 13] or conditions such as diverticulitis [3, 12, 14, 17] may be suspected causes of urachus-intestinal fistulas. Less frequent signs and symptoms have been reported, such as subcutaneous emphysema of the abdomen and thorax [21] and pneumaturia associated with fecaluria [1]. Only two reported cases did not present fecal discharge through the umbilicus. In children, primarily stricturing or penetrating Crohn’s disease is reported as an important cause of these fistulas, even involving other intestinal segments such as the cecum and ileum [5].

The diagnosis of these fistulas generally involves the use of ultrasonography and computed tomography, which are effective in identifying urachal anomalies and their complications. Additionally, magnetic resonance imaging and cystoscopy can be utilized in complex cases [9, 22]. In this case, the diagnosis was made through computed tomography, which initially revealed the presence of an umbilical hernia and an infected urachal cyst. The progression of the condition revealed the fistula with the sigmoid colon after one year, with a new CT scan clearly demonstrating the uracho-sigmoid- cutaneous fistula. Similarly, other cases in the literature initially presented with isolated urachal abnormalities that later evolved into complications with fistulas to the colon, indicating that the initial condition may be underdiagnosed. [19, 21]

The treatment of uracho-intestinal fistula is predominantly surgical, involving complete excision of the fistulous tract, the urachal remnant, and the affected intestinal segment en bloc, as described by various authors [1, 12, 14, 17, 19]. In cases of active infection or abscess formation, a two-stage approach is often recommended due to the risk of surgical site infection, which is more common when primary excision is performed in an infectious setting [6]. In this case, a 7-day course of oral ciprofloxacin and metronidazole was administered prior to surgery and continued until the 7th postoperative day, with no occurrence of surgical site infection. Few authors describe the duration of antibiotic therapy used, which varies from 4 to 6 weeks, including the preoperative and postoperative periods [12, 13].

Regarding surgical techniques, the laparoscopic approach has been described as a viable and safe alternative, offering advantages such as lower morbidity, shorter hospital stay, and better aesthetic outcomes [6]. Three reported cases of uracho-intestinal fistula were managed laparoscopically with good outcomes [14, 17, 19], although one patient was discharged 9 days after surgery, compared to 7 days in the present case, which was managed via laparotomy. Laparoscopy allows for detailed visualization of the anatomy and the extent of the fistula [6]. Nevertheless, laparotomy performed through a transumbilical, infraumbilical, or transverse incision remains widely used, especially in complex cases or those with extensive infection, where broad excision is required [6, 12].

The decision regarding primary anastomosis of the colon is not described in all reported cases. However, when performed, it appears to yield good outcomes, as observed in the present case [10, 14, 17]. Additionally, there is a report of primary anastomosis with loop ileostomy in one case [3]. The choice of technique depends on the patient's clinical condition, the surgeon's experience, and the availability of resources.

Conclusion

Cases of uracho-sigmoid-cutaneous fistula are extremely rare in adults and are surgically treated with a block resection of the fistula along with the associated viscera. The approach can be either laparoscopic or open surgery, depending on resource availability and the patient’s clinical condition. Primary colonic anastomosis appears to be safe when clinical conditions are favorable. In this case report, which involved a chronic evolution, treatment was performed via laparotomy after 7 days of antibiotics, with an bloc partial colon resection including the fistula, followed by primary anastomosis and an additional 7 days of antibiotics, without complications.

References

- Coons BJ, Clark PE, Maynes LJ, Terhune KP, Stokes MC, et al. (2009) Sigmoid–Urachal–Cutaneous Fistula in an Adult Male. Urology. 73(2): 444.e5-7.

- Corsello J, Morris M, Denning D, Munie S (2021) Case of infected urachal cyst in an adult presenting as an incarcerated umbilical hernia. The American Surgeon. 88(5): 997–999.

- Dickhoff C, Campo MM, Ophof PJ, Makkus AF, Tan KG, et al. (2008) Urachus Fistula: A Rare First Presentation of Diverticulitis.. Case reports in gastroenterology 2(3): 287-90.

- Flanagan DA, Mellinger JD (1998) Urachal-sigmoid fistula in an adult male. The American Surgeon. 64(8): 762-763.

- Herrick-Reynolds KM, Steinhauser CM, Singla M, Kucera WB, Wind GG, et al. (2021) Entero-Urachal Fistula: an unusual initial presentation of penetrating and stricturing crohn’s disease. The American Surgeon™. 89(6): 2794-2796.

- Hurreiz H, Hussain I, Hamo I (2006) Urachal fistula presenting as umbilical sepsis: a rare case in an adult male. Med Sci Monit. 12(5): CS44-7.

- Jayakumar S, Darlington D (2020) Acute Presentation of Urachal Cyst: a case report. Cureus. 12(5): e8220.

- Keçeli AM, Dönmez Mİ (2021) Are urachal remnants really rare in children? An observational study. European Journal of Pediatrics. 180(6): 1987–1990.

- Lipskar AM, Glick RD, Rosen NG, Layliev J, Hong AR, et al. (2010) Nonoperative management of symptomatic urachal anomalies. Journal Of Pediatric Surgery. 45(5): 1016-1019.

- Peters AL, Kruijer MJ, Wiese H, Verbeek PC (2012) A colo- urachal-cutaneous fistula in an 88-year-old male. International Journal Of Surgery Case Reports. 3(2): 55-58.

- Portela A.R, Nishmoto R.H, Palma M.C, Salles R.L.A (2016) Cisto de úraco infectado como diagnóstico diferencial na dor abdominal e abordagens terapêuticas. Revista Urominas. 61-65.

- Rapoport D, Ross A, Goshko V, McAuley I (2007) Urachal- sigmoid fistula associated with diverticular disease. Canadian Urological Association Journal. 1(1): 52-4.

- Rebai W, Ksantini R, Abdelhedi C, Chebbi F, Gargouri M, et al. (2011) Fistule colo-cutanée d'origine allantoïde chez un adulte [Colo-urachal-cutaneous fistula in an adult]. Tunis Med. 89(5): 476-478.

- Sakata S, Grundy J, Naidu S, Gillespie C (2016) Urachal-sigmoid fistula managed by laparoscopic assisted high anterior resection, primary anastomosis and en bloc resection of the urachal cyst and involved bladder. Asian J Endosc Surg. 9(3): 201-203.

- Mafra SCR, Salgado CS, Araújo MP, Lopes LG, de Oliveira RSCPM, et al. Tratamento Cirúrgico de Cisto de Úraco - Relato de Caso e Revisão de Literatura.

- Schurmans R CP, Olij B, Kool M, Weinans CRGJ, Visschers RGJ, Zijta F, et al. (2018) Infected urachal cyst in an adult patient. Journal of Clinical Ultrasound. 52(9): 1490-1494.

- Soyster M, Ristau BT, Girard ED, Liang Y, Hegde P, et al. (2018) An unlikely connection: Rare case of colo-urachal fistula, surgical management, and review of the literature, Urology Case Reports. 18: 9-10.

- Sukiman B, Santiana L (2024) An infected urachal cyst forming an abscess: A case report. Radiol Case Rep. 19(12): 5926-5931.

- Tomida A, Hattori M, Hirata A, Shibata J, Imataki H, et al. (2025) A Rare Case of Sigmoid‐Urachal Fistula in an Adult Male Resected Laparoscopically. Asian J Endosc Surg. 18(1): e70024.

- Torres LRP, Fernandes LVP, Borges DEM, Costa C (2020) Remanescentes do úraco: uma revisão da literatura direcionada à abordagem cirúrgica. Integrantes da coordenação científica. 7.

- Yang D, Pearson D, Smith D (2020) A rare case of a diverticular perforation associated with colo-urachal fistula presenting as anaphylaxis. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 102(3): e51-e53.

- Yoo KH, Lee SJ, Chang SG (2006) Treatment of Infected Urachal Cysts. Yonsei Medical Journal. 47(3): 423-7.