Kudzai Patience Takarinda1, Simon Nyadundu2, Addmore Chadambuka1*, Emmanuel Govha1, Notion Tafara Gombe3, Mujinga Karakadzai4, Tsitsi Juru1, Mufuta Tshimanga1

1Department of Primary Health Care Sciences, Global and Public Health Unit, University of Zimbabwe

2Zimbabwe Ministry of Health and Child Care, Provincial Medical Directorate, Manicaland

3African Field Epidemiology Network, Harare, Zimbabwe

4Zichire Project

*Corresponding Author: Addmore Chadambuka, Department of Primary Health Care Sciences, Global and Public Health Unit, University of Zimbabwe

Abstract

Background: Data from the District Health Information System (DHIS-2) for Zimbabwe showed that Manicaland Province had the highest proportion of sexual abuse reports in 2020 accounting for 1744(16 %). Mutare District accounted for 590 (37 %) of all cases in the Province and 557(94 %) were referred to Victoria Chitepo Provincial Hospital (VCPH) Victim Friendly Unit. We described the characteristics and outcomes of sexual abuse survivors.

Methods: We conducted a retrospective cross-sectional study based on a review of 1,102 medical affidavits completed between January 2019- December 2020 and annual reports. Epi Info version 7 was used to generate frequencies, proportions, and logistic regression analysis.

Results: Female survivors constituted 1048/1102 (95 %) and 433/1048 (41%) were aged between 13-15 years. Only 234 (21 %) survivors presented within 72 hours. Factors associated with presentation within 72 hours were survivors aged 25-44 years [OR=3.12,(95 % CI,1.51- 6.46)], and being assaulted by a stranger [OR=3.87 (95 % CI,2.3-6.52)]

Conclusion: Access to medical care within 72 hours remains a challenge.

Keywords: Sexual Violence, COVID 19, Post-exposure prophylaxis, Zimbabwe

Introduction

Sexual violence is a pervasive public health issue in all societies [1]. It is defined as any sexual act, attempt to obtain a sexual act, unwanted sexual comments, or advances directed against a person’s sexuality using coercion [2]. Sexual violence can be perpetrated by any person regardless of the relationship to the survivor, in any setting, and is committed against both men and women [2]. Sexual violence encompasses verbal harassment, forced penetration, and includes unwanted sexual advances, rape within marriage, dating relationships, or by strangers, and acquaintances [3].

Sexual abuse prevalence estimates

Globally, 1 in 3 women, (approximately 736 million) have experienced either physical and/or sexual violence in their lifetime [4]. Worldwide estimates suggest that 7 % of women have been sexually assaulted by someone other than a partner [5]. Despite the vast majority of survivors being women, men, and children of both genders also experience sexual violence. Between 8 %, and 31 % of girls compared to 3 %, and 17 % of boys experience childhood sexual violence worldwide [6]. People with disabilities are two times more likely to encounter sexual victimization than nondisabled individuals [7]. Sexual minority populations are also at a disproportionate risk of experiencing sexual violence [8].

Variations exist in the prevalence estimates of sexual violence across different regions. In the world’s high-income countries, the prevalence of intimate partner, and/or non-partner sexual violence among women aged 15-49 years averages 30 % [4]. In low, and middle-income countries the prevalence ranged from 25 % in the Western Pacific Region to 36 % in the African Region [4].

The Zimbabwe Demographic Health Survey Report of 2015 indicates that 14 % of women aged 15-49 years have experienced sexual violence at some point in their lives [9]. The 2011 baseline survey on life experiences of adolescents indicates that 1 in 10 males experience sexual violence prior to age 18 years [10]. According to the Zimbabwe Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey for 2019, five percent of women aged 20-24 years were first married or in union before age 15 and 34 % before they reached 18 years [11].

Consequences of sexual violence

Sexual violence results in multiple physical and psychological consequences [2]. About 2–39 % of female survivors of rape are diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [12]. Sexual violence is also associated with substance abuse, high-risk behaviors, and an increased risk of becoming a perpetrator. Sexual violence has substantial costs with some countries spending an estimated 3.7 % of their GDP on direct health and justice system costs as well as indirect costs of lost productivity [5].

Zimbabwe guidelines for the care needs of victims of sexual assault

The Criminal Procedure and Evidence Amendment Act [Chapter 9:07] of 1997 prompted the establishment of the Victim Friendly System (VFS) in Zimbabwe aimed at supporting survivors of sexual abuse to pursue their right to access specialized health, justice, and welfare services. The multi-sectorial protocol on the management of child sexual abuse developed in 2003, and reviewed in 2012 provides guidance on sector agencies’ roles, and responsibilities [13]

While it is essential that all cases of sexual assault are reported to the police, a police report is not a prerequisite for receiving medical care. A survivor of sexual abuse who presents at the victim-friendly unit is attended to by a doctor or nurse who then takes the history of the event, examines the survivor, and completes a medical affidavit. Information that is collected when a client presents at the health facility includes age, gender, type of aggressor, type of assault, time of client presentation, results of medical examinations, and care administered for the mitigation of medical consequences of sexual violence. Survivors of sexual abuse should be offered a standardized package of free medical and psychosocial care including referral for termination of pregnancy and legal support. The medical affidavit is presented as evidence in a victim-friendly court (VFC) if the perpetrator is prosecuted.

Data from the District Health Information System (DHIS-2) for the year 2020 showed that Manicaland Province in Zimbabwe recorded the highest proportion of sexual abuse cases constituting 1744/10 627(16 %) of survivors. Mutare District had the highest number of sexual abuse survivors 590/1578 (37 %) who interfaced with the healthcare system in 2020. The majority of cases, 557/590 (94 %) were attended at Victoria Chitepo Provincial Hospital Victim Friendly Unit (VFU).

We described the characteristics, and outcomes of sexual assault survivors presenting at Victoria Chitepo Provincial Hospital Victim Friendly Unit (VFU), Manicaland Province, Zimbabwe from 2019- 2020. Our specific objectives were to describe the socio-demographic characteristics and clinical signs and symptoms of sexual assault survivors. We described the types of sexual assault and their relationship to aggressors per age group. We determined the factors associated with survivor presentation within 72 hours and described the proportion of clients receiving clinical care, prophylactic, and psychosocial support services. An analysis of the characteristics and outcomes of survivors of sexual abuse will aid in identifying areas that can be improved as well as gaps in service provision. The aggressor profile analysis gives an insight into the design of targeted interventions that aim to prevent sexual violence in the community.

Methods

Study design and study setting

We conducted a retrospective cross-sectional study based on a review of medical affidavits at the VCPH Victim Friendly Unit. We included medical affidavits completed between January 2019, and December 2020. Our study setting was Victoria Chitepo Provincial Hospital which is the only tertiary hospital in Manicaland Province where all the sexual assault cases in Mutare District are referred. The Ministry of Health and Child Care (MOHCC) partnered with Family Support Trust (FST), a non-governmental organization (NGO) to offer services to survivors of sexual assault in a survivor-friendly environment at VCPH Victim Friendly Unit.

Data collection and definition of variables

We used a data abstraction tool to collect the study variables from the medical affidavits. Reviewed medical affidavits had the patient demographic-, medical examination-, external examination-, genital examination- and evidence-of-penetration sections completed. The following sections were not completed on all medical affidavits: medical history of sexual abuse- previous medical history-, prophylaxis and treatment provided-, and follow-up care. Information on the relationship of the aggressor was obtained from a separate register for all survivors while information on care and treatment of survivors was obtained from annual reports. Our dependent variable which is the primary outcome of interest was survivor presentation to the victim-friendly unit within 72 hours of the sexual assault. The independent variables in our study were patient demographic information which included age, sex, and marital status as well as mental development for age, and secondary sexual development. Data on time to presentation was categorized as 0-24 hours, 1-3 days, 4-7 days, 8-30 days, 1-3 months, > 3 months, and unknown duration. The unknown duration was when a survivor of sexual violence could not recall the time when the assault occurred. Data on the clinical evidence of sexual penetration was categorized as definite, very likely, probable, inconclusive but possible, and no visible evidence.

Signs and symptoms of sexual violence included hymenal tears, stretched hymen, genital discharge, genital bleeding, anal bruises, uterine tenderness, genital sores, anal abnormal skin folds, genital warts, reflex anal dilation, and anal venous congestion. Clinical management included HIV post-exposure prophylaxis, emergency contraception, prophylactic antibiotics, counseling, and psychosocial support. Laboratory tests offered to survivors were a baseline HIV test, a rapid diagnostic test for syphilis, a high vaginal swab for culture, and sensitivity, and a pregnancy test.

Data analysis

We used Epi Info vs. 7 for capturing data and to generate frequencies, medians, and proportions. Bivariate analysis and multivariate logistic regression were used to test the presence and strength of association between presenting to the Victim Friendly Unit with 72 hours, and, age, and sex of the survivor, type of assault, and relationship to the aggressor. Odds ratio and 95 % confidence intervals were generated. Significance was taken as p-value < 0.05.

Ethical considerations

We obtained permission to conduct the study from the Provincial Medical Director (PMD) Manicaland Province, Medical Superintendent Victoria Chitepo Provincial Hospital, Health Studies Office Ministry of Health, and Child Care and Family Support Trust Manager. The names of healthcare workers and survivors of sexual abuse were kept confidential by assigning matching and anonymous identification numbers to the medical affidavit and the data abstraction form during data collection.

Results

We analyzed 1, 102 medical affidavits available for the period January 2019 to December 2020. The overall completeness of medical affidavits was 60 %.

Socio-demographic characteristics of sexual assault survivors

Females accounted for 1048/1102 (95 %) survivors with a median age group of 14 years. The median age for males was 9 years. The dominant age group of sexual abuse survivors for females was 13-15 years which constituted 433/1048 (41 %) of survivors. The majority of male sexual abuse survivors, 29/49 (59 %) were in the 5-12-year age group. Among females, 44/1048 (4 %) were mentally impaired. Female survivors were mostly at the pubertal stage constituting 589/1048 (56 %) while males, 34/49 (70 %) were predominantly pre-pubertal. There were 5 records that had missing sex and were excluded from table 1 (Table 1).

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of sexual assault survivors presenting at VCPH Victim Friendly Unit 2019-2020

|

Variable |

Female |

Male |

|||

|

|

|

n=1048 |

% |

n=49 |

% |

|

Age at encounter (Years)

|

0-4 |

62 |

6 |

5 |

10 |

|

5-12 |

243 |

23 |

29 |

59 |

|

|

13-15 |

433 |

41 |

6 |

12 |

|

|

16-24 |

196 |

19 |

2 |

4 |

|

|

25-44 |

65 |

6 |

3 |

6 |

|

|

≥45 |

2 |

<1 |

1 |

2 |

|

|

Not recorded |

47 |

5 |

3 |

6 |

|

|

Median (Interquartile range Q1-Q3) |

14 (11-16) |

9 (6-13) |

|||

|

Marital status |

Child under 16 |

807 |

77 |

41 |

84 |

|

Single |

159 |

15 |

4 |

8 |

|

|

Married |

43 |

4 |

3 |

6 |

|

|

Divorced |

4 |

<1 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

Widowed |

14 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

Not recorded |

21 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

|

|

Mental development for age |

Normal |

1002 |

96 |

48 |

98 |

|

Impaired |

44 |

4 |

1 |

2 |

|

|

Not recorded |

2 |

<1 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

Secondary sexual development |

Pre-pubertal |

237 |

23 |

34 |

70 |

|

Pubertal |

589 |

56 |

8 |

16 |

|

|

Mature |

220 |

21 |

7 |

14 |

|

|

Post-menopausal |

2 |

<1 |

|

|

|

Type of sexual assault among sexual abuse survivors

The dominant type of assault among all age groups was rape constituting 538/1102 (49 %) followed by suspected abuse among 283/1102 (26 %) survivors. Sex with a minor (child /under 16 years) constituted 137/1102 (12 %) of assaults. Minor to minor sexual assaults constituted 50/1102 (5 %). Aggravated indecent assault and attempted rape accounted for 35/1102 (3 %) and 30/1102 (3 %) respectively while a total of 29/1102 (3 %) medical affidavits had missing information.

Among the 0-4-year age group, the most frequent type of sexual assault was rape constituting 26/67 (39 %) followed by aggravated indecent assault 8/67 (12 %). Among the 5-12-year age group, the most frequent type of sexual assault was suspected abuse accounting for 113/272(42 %) followed by rape 108/272 (40 %). The most frequent sexual assault amongst the 13-15-year age group was rape constituting 170/442 (38 %) followed by sex with a minor which constituted 126/442 (29 %). Amongst the 16-24-year age group, rape was the most frequently reported assault accounting for 162/200 (81 %). Fifty records with missing age were excluded from this analysis (Table 2).

Table 2: Type of sexual assault by age group among sexual abuse survivors presenting at VCPH Victim Friendly Unit 2019-2020

|

|

0-4 years |

5-12 years |

13-15 years |

16-24 years |

25-44 Years |

≥45 years |

||||||

|

Type of Assault |

n=67 |

% |

n=272 |

% |

n=442 |

% |

n=200 |

% |

n=68 |

% |

n=3 |

% |

|

Sex with a minor |

0 |

0 |

11 |

4 |

126 |

29 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Attempted rape |

2 |

3 |

9 |

3 |

12 |

3 |

4 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

|

Rape |

26 |

39 |

108 |

40 |

170 |

38 |

162 |

81 |

45 |

66 |

3 |

100 |

|

Aggravated indecent assault |

8 |

12 |

15 |

5 |

6 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

|

Minor to minor |

5 |

6 |

14 |

5 |

26 |

6 |

4 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Suspected abuse |

26 |

39 |

113 |

42 |

97 |

22 |

22 |

11 |

7 |

10 |

0 |

0 |

|

Missing |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

5 |

1 |

7 |

3 |

13 |

19 |

0 |

0 |

Relationship to aggressor among sexual assault survivors

Most sexual assaults were perpetrated by a boyfriend, 288/1062 (27%) followed by a relative constituting 270/1062 (25 %). A neighbor or co-tenant accounted for 199/1062 (19 %) of sexual assaults. Sexual assaults by strangers constituted 93/1062 (9 %) while those by a religious leader accounted for 36/1062 (3 %).

Relationship to aggressor per age group

Among the 0-4-year age group, the dominant aggressor was a relative accounting for 40/67 (60 %). Similarly, for the 5-12-year age group, the dominant aggressor was a relative 113/272 (42 %) followed by a neighbor/co-tenant, 85/272 (31 %). Among the 13-15-year age group, the dominant aggressor was a boyfriend 207/442 (47 %). Among the 16-24 age group, the most frequently reported aggressor was a boyfriend 49/200 (24 %) followed by a religious leader 26/200 (13 %). The dominant aggressor amongst the 25-44-year age group was a stranger 19/68(28 %) (Table 3).

Table 3: Relationship to aggressor by age group for sexual assault survivors presenting at VCPH Victim Friendly Unit 2019-2020

|

Relationship to Aggressor |

0-4 Years |

5-12 Years |

13-15 years |

16-24 Years |

25-44 Years |

≥ 45 Years |

||||||

|

|

n=67 |

% |

n=272 |

% |

n=442 |

% |

n=200 |

% |

n=68 |

% |

n=3 |

% |

|

Relative |

40 |

60 |

113 |

42 |

72 |

16 |

25 |

13 |

4 |

6 |

0 |

0 |

|

Stranger |

3 |

5 |

16 |

6 |

27 |

6 |

24 |

12 |

19 |

28 |

2 |

67 |

|

Boyfriend |

0 |

0 |

13 |

5 |

207 |

47 |

49 |

24 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

|

Neighbour/Co-tenant |

13 |

19 |

85 |

31 |

61 |

14 |

22 |

11 |

5 |

7 |

1 |

33 |

|

Employer |

0 |

0 |

1 |

<1 |

5 |

1 |

16 |

8 |

9 |

13 |

0 |

0 |

|

Religious person |

0 |

0 |

7 |

3 |

12 |

3 |

26 |

13 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

|

Friend |

0 |

0 |

1 |

<1 |

7 |

2 |

6 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

|

Known/No relation |

2 |

3 |

20 |

7 |

27 |

6 |

8 |

4 |

5 |

7 |

0 |

0 |

|

Husband |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4 |

1 |

11 |

5 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

|

Intimate partner |

0 |

0 |

1 |

<1 |

0 |

0 |

8 |

4 |

14 |

21 |

0 |

0 |

|

Domestic worker |

9 |

13 |

9 |

3 |

6 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

|

Teacher |

0 |

0 |

6 |

2 |

14 |

3 |

4 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Clinical signs and symptoms of sexual assault survivors

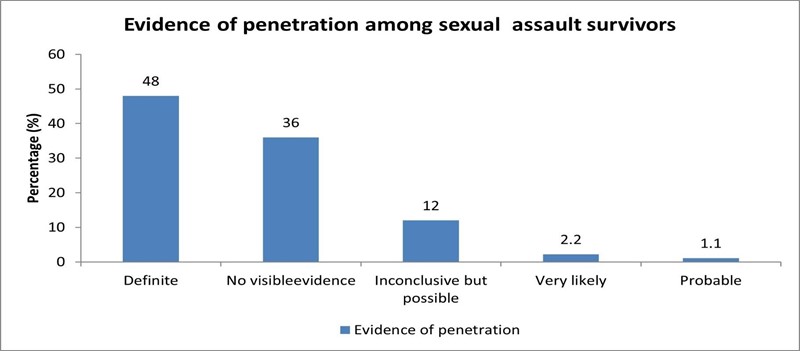

We found that the most frequently reported symptom of a sexually transmitted infection among sexual abuse survivors was abnormal genital discharge 177/1102 (16 %) followed by genital sores 47 (4 %). Genital warts were reported for 28 (3 %) of survivors while 13 (1 %) presented with pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). Signs and symptoms of sexual abuse included hymenal tears reported for 375/1102 (34 %) of survivors, followed by 214 (19 %) who presented with a stretched hymen. The least reported clinical symptom of sexual abuse was anal venous congestion reported for 3 (0.3 %). The majority of sexual abuse survivors 530/1102 (48 %) had definite evidence of penetration, while 395/1102 (36 %) had no visible evidence of penetration followed by survivors with inconclusive but possible evidence of penetration constituting 136/1102 (12 %) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Evidence of penetration among sexual violence survivors presenting at VCPH Victim Friendly Unit 2019-2020

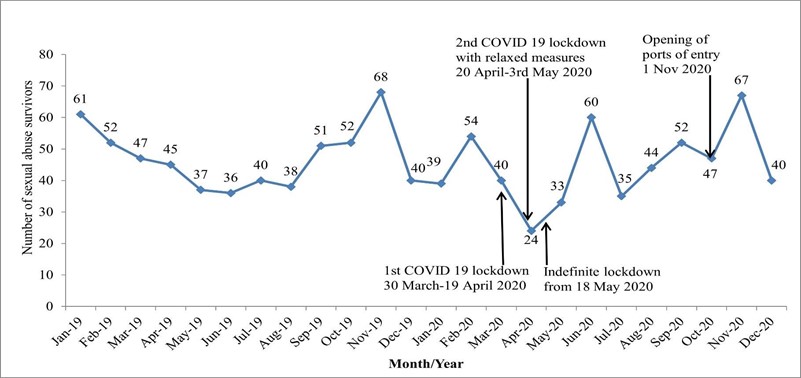

Monthly trends in the number of sexual assault survivors 2019-2020

There was a 41 % decline in the number of reported sexual abuse survivors presenting at the VCPH Victim Friendly Unit from 61 cases in January 2019 to 36 cases by the end of June 2019. Thereafter, the number of survivors increases steadily reaching a peak of 68 reported cases in November 2019 and further declines nearly 3-fold to 24 cases by the end of April 2020. This followed the first level-five COVID 19 national lockdown instituted by the Government of Zimbabwe from 30 March-19 April 2020. The lockdown measures were relaxed in stages, and an indefinite lockdown was instituted from 18 May 2020. The number of reported sexual abuse survivors steadily increased to 60 cases by the end of June 2020. Overall, there was a 5 % decline in the number of sexual abuse survivors from 165 between March-June 2019 compared to 157 during the same lockdown period in 2020. The highest number of sexual assaults (67 cases) was reported in November 2020 following the opening of the points of entry on the 1st of November 2020. Overall, there was a 5.6 % decrease in the number of sexual abuse survivors from 567 reports in 2019 compared to 535 in 2020. (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Monthly trends in the number of sexual abuse survivors presenting at VCPH Victim Friendly Unit 2019-2020

Time to presentation among sexual assault survivors

Out of 1102 medical affidavits analyzed, only 234 (21 %) sexual assault survivors presented within the recommended 72 hours. Only 38(3 %) survivors reported within 24 hours, 196 (18 %) within 1-3 days, 122 (11 %) within 4-7days, 174 (16 %) between 8-30 days, 125 (11 %) within 1-3 months, and 115 (10 %) reported within 3 months of the sexual assault. The majority of survivors presenting at Victoria Chitepo Provincial Hospital did not know the period of time lapsed after the assault 332(30 %).

Sexual assault reporting within 72 hours by age group

The majority of adults aged 25 years and above 37 (51 %) reported within 72 hours compared with 17 (25 %) of children aged 0-4 years. The 5-12-year age group had the lowest proportion of survivors presenting within 72 hours 38/272 (14 %) followed by the 13-15 year age group 76/442 (17 %) and this was statistically significant (p < 0.001). The relationship between sex and presentation within 72 hours was not statistically significant (p = 0.83). The proportion of survivors presenting within 72 hours was lowest among children under 16 years compared to adults and this was statistically significant (p<0.001) (Table 4).

Table 4: Socio-demographic characteristics, type, and relationship to aggressor versus presentation within 72 hours for sexual violence survivors presenting at VCPH VFU 2019-2020

|

Variable |

Total |

> 72 hours |

=/< 72 hours |

P-value |

||

|

|

N |

Percentage |

n |

Percentage |

||

|

Age group |

|

|||||

|

0-4 years |

67 |

50 |

75 |

17 |

25 |

<0.001 |

|

5-12 years |

272 |

234 |

86 |

38 |

14 |

|

|

13-15 years |

442 |

366 |

83 |

76 |

17 |

|

|

16-24 years |

200 |

144 |

72 |

56 |

28 |

|

|

25-44 years |

68 |

33 |

49 |

35 |

51 |

|

|

≥45 years |

3 |

1 |

33 |

2 |

67 |

|

|

Sex |

|

|||||

|

Female |

1048 |

826 |

79 |

222 |

21 |

0.83 |

|

Male |

49 |

38 |

78 |

11 |

22 |

|

|

Marital Status |

|

|||||

|

under 16 years |

850 |

705 |

83 |

145 |

17 |

< 0.001 |

|

Single |

164 |

114 |

70 |

50 |

30 |

|

|

Married |

47 |

26 |

55 |

21 |

45 |

|

|

Widowed |

4 |

1 |

25 |

3 |

75 |

|

|

Divorced |

14 |

6 |

43 |

8 |

57 |

|

|

Type of assault |

|

|||||

|

Sex with a minor |

137 |

14 |

83 |

23 |

17 |

0.75 |

|

Attempted rape |

30 |

25 |

83 |

5 |

17 |

|

|

Rape |

538 |

418 |

78 |

120 |

22 |

|

|

Aggravated indecent assault |

35 |

29 |

83 |

6 |

17 |

|

|

Minor to minor |

50 |

40 |

80 |

10 |

20 |

|

|

Suspected abuse |

283 |

224 |

79 |

59 |

21 |

|

|

Type of aggressor |

|

|||||

|

Relative |

270 |

228 |

84 |

42 |

16 |

< 0.001 |

|

Stranger |

93 |

53 |

57 |

40 |

43 |

|

|

Boyfriend |

288 |

242 |

84 |

46 |

16 |

|

|

Neighbour/ Co-tenant |

199 |

162 |

81 |

37 |

19 |

|

|

Employer |

27 |

16 |

59 |

11 |

41 |

|

|

Religious person |

36 |

30 |

83 |

6 |

17 |

|

|

Friend |

17 |

13 |

76 |

4 |

24 |

|

|

Known No relation |

65 |

50 |

77 |

15 |

23 |

|

|

Husband |

18 |

16 |

89 |

2 |

11 |

|

|

Intimate partner |

17 |

10 |

59 |

7 |

41 |

|

|

Domestic worker |

19 |

10 |

53 |

9 |

47 |

|

|

Teacher |

18 |

17 |

94 |

1 |

6 |

|

Factors associated with presentation within 72hrs among sexual abuse survivors

Compared to the 0-4-year olds, those aged 5-12 years were 52 % less likely to present at Victoria Chitepo Hospital 72 hours after their sexual abuse encounter [OR=0.48, (95 % CI, 0.25-0.91)]. However, those aged 25-44 years were three times more likely to present within 72 hours [OR=3.12, (95 % CI, 1.51-6.46)]. In comparison to children <16 years, being single [OR=2.13 (95 % CI, 1.46-3.11)], married [OR=3.93 (95 % CI, 2.15-7.17)], widowed [OR=14.6 (95 % CI, 1.51-141.22)], and being divorced [OR=6.48 (95 % CI, 2.22-18.97)] were all associated with higher odds of presenting to a health facility within 72 hours of a sexual abuse encounter (Table 5).

Sexual assaults by a stranger were 3.9 times more likely to be presented within 72 hours [OR=3.87 (95 % CI,2.3-6.52)] and those assaulted by an employer were 3.5 times more likely to present within 72 hours [OR=3.53 (95 % CI, 1.54-8.11)]. Those sexually assaulted by a domestic worker were 4.6 times more likely to present within 72 hours [OR=4.62 (95 % CI, 1.78-12.01)]. When the aggressor was a husband, presentation within 72 hours was 36 % less likely, however, this was not statistically significant [OR=0.64 (95 % CI, 0.14-2.89)] (Table 5).

Table 5: Factors associated with presentation within 72 hours at VCPHVFU 2019-2020

|

Variable |

Outcome |

Number (N) |

Present within 72 hours |

OR |

(95% CI) |

|

|

n |

% |

|||||

|

Age group |

0-4 years |

67 |

17 |

25 |

Reference |

|

|

5-12 years |

272 |

38 |

14 |

0.48 |

(0.25-0.91) |

|

|

|

13-15 years |

442 |

76 |

17 |

0.61 |

(0.33-1.12) |

|

|

16-24 years |

200 |

56 |

28 |

1.14 |

(0.61-2.15) |

|

|

25-44 years |

68 |

38 |

52 |

3.12 |

(1.51-6.46) |

|

|

≥ 45 years |

3 |

2 |

66 |

5.88 |

(0.50-69.04) |

|

|

Not recorded |

50 |

10 |

20 |

- |

- |

|

Marital Status |

Child < 16 years |

850 |

145 |

17 |

Reference |

|

|

Single |

164 |

50 |

31 |

2.13 |

(1.46-3.11) |

|

|

|

Married |

47 |

21 |

45 |

3.93 |

(2.15-7.17) |

|

|

Widowed |

4 |

3 |

75 |

14.59 |

(1.51-141.22) |

|

|

Divorced |

14 |

8 |

57 |

6.48 |

(2.22-18.97) |

|

|

Missing |

23 |

7 |

30 |

- |

- |

|

Type of aggressor |

Relative |

276 |

45 |

16.3 |

Reference |

|

|

Stranger |

93 |

40 |

43 |

3.87 |

(2.3-6.52) |

|

|

|

Boyfriend |

277 |

43 |

15.5 |

0.94 |

(0.6-1.49) |

|

|

Neighbour/ Co-tenant |

199 |

37 |

18.59 |

1.17 |

(0.73-1.89) |

|

|

Employer |

27 |

11 |

40.74 |

3.53 |

(1.54-8.11) |

|

|

Religious person |

36 |

6 |

16.67 |

1.03 |

(0.4-2.61) |

|

|

Friend |

17 |

4 |

23.53 |

1.58 |

(0.49-5.07) |

|

|

Known no relation |

65 |

15 |

23.1 |

1.54 |

(0.8-2.98) |

|

|

Husband |

18 |

2 |

11.1 |

0.64 |

(0.14-2.89) |

|

|

Intimate partner |

17 |

7 |

41.2 |

3.59 |

(1.30-9.94) |

|

|

Domestic worker |

19 |

9 |

47.4 |

4.62 |

(1.78-12.01) |

|

|

Teacher |

18 |

1 |

5.6 |

0.3 |

(0.04-2.33) |

|

|

Missing |

31 |

40 |

14 |

- |

- |

Clinical care, and psychosocial support services received by survivors of sexual assault

Out of the 1102 medical affidavits analyzed, 942 (85.5 %) were tested for HIV, and 22 (2.3 %) tested positive. We found that 66 (6 %) survivors were re-tested for HIV at the 3 months follow-up visit and there were no seroconversions among this subgroup. A total of 341 (54.3 %) females were tested for pregnancy and 113 (33.1 %) had a positive pregnancy test. A rapid syphilis test was performed for 906 (82.2 %) survivors and 210 (23.2 %) tested positive. Samples for forensic examination were taken for 2 (0.2 %) survivors. Vaginal swabs were collected for 162 (91.5 %) of survivors presenting with abnormal vaginal discharge.

A total of 110 sexual assault survivors were eligible for post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), however, 70 (63.6 %) received PEP for HIV. Out of a total of 48 sexual assault survivors who were eligible, 26 (54 %) were given emergency contraception. Prophylactic antibiotics were given to 176/210 (84 %) of survivors. All 1102 clients received counseling and psychosocial support on first contact however, 374 (33.9 %) received follow-up visits for the period. Recorded were 182 home and 192 telephone follow-up visits.

Discussion

Our analysis of medical affidavits at Victoria Chitepo Provincial Hospital Victim Friendly Unit showed that most sexual abuse survivors were females aged 13-15 years. This may be a result of traditional, religious, and sociocultural norms potentially driven by economic motives that contribute to gender inequality and expose young females to sexual abuse [14]. The 2017 sexual violence report published by Médecins Sans Frontiers (MSF) also showed that adolescent females in the 13–15-year age group account for the majority of female survivors in Harare [14].

The age distribution of survivors of sexual assault showed a distinct difference as the majority of male survivors were in the 5-12-year age group. The 2017 sexual violence report published by Médecins Sans Frontiers (MSF) however showed that the largest number of male survivors came from the age group of 2-5 years [14]. Our findings are in agreement with Broban et al, 2020 who also found that child cases were more likely to be males, while adolescents were more likely to be female [15]. Documented statistics are unlikely to provide an accurate picture of the true scale of sexual violence due to underreporting, particularly by male survivors [16]. Barriers that prevent males from reporting sexual abuse include stigma, fear of not being believed, and self-blame regarding the inability to prevent what happened or being labeled as homosexual [17].

The majority of survivors showed normal mental development for age, however, Bryne, 2018 confirmed that children and adults with an intellectual disability are at a higher risk of sexual abuse than non-disabled peers [18]. Communication barriers contribute towards under-reporting of sexual abuse among individuals with intellectual disability [19].

About a third of survivors presented with hymenal tears after sexual assault. This is consistent with Adams et al, 2018 who found that the prevalence of injuries was 21.4 % among sexually abused girls examined acutely [20]. Rapid healing of mucous tissue particularly in children results in the majority of sexually abused children not displaying signs of penetrative trauma at anogenital examination [21].

The majority of sexual assaults were perpetrated by individuals that were known to the victim. A relative was the most reported aggressor for children aged 12 years and below while a boyfriend was predominantly reported by the 13-15-year age group. This high proportion could be associated with the high number of forced first sexual intercourse and age-disparate sexual relationships leading to power imbalances that are associated with sexual coercion and sexual violence [22]. This agrees with Tapesana et al, 2017 who showed that three-quarters of sexual assault survivors demonstrated a relationship with the perpetrators and a boyfriend was the aggressor in a third of sexual assaults [23].

We found that there was a decline in the number of medical affidavits recorded during the Covid 19 lockdown movement restrictions followed by a significant increase as the lockdown measures were relaxed. This may reflect the negative impact of lockdown restrictions on access to essential services particularly by children in our setting. Analysis of gender-based violence (GBV) data in Zimbabwe by Martin & Ahlenback, 2020 during the lockdown period from March-May 2020 reported a decrease in absolute numbers of non-partner violence assaults compared to the same period in 2019 owing to reduced contact with non-partner perpetrators, however, an increase in child marriages was recorded [24]. Overall, there was a decrease in the absolute number of sexual assault survivors presenting at the victim-friendly unit between the period March to June 2019 compared to the same period in 2020. This is despite societal conditions that elevated the risk of sexual abuse due to the COVID 19 pandemic lockdown restrictions including lack of a protective environment in schools, household food insecurity, and economic instability. This is contrary to findings by Mekaoui et al in 2021 who found a 230 % increase in child sexual abuse cases during the lockdown period of March to June 2020 in Morocco compared to the same period in 2019 [25].

The majority of survivors presented to the victim-friendly unit after 72 hours and therefore did not receive post-exposure prophylaxis or emergency contraception. This is in agreement with Kufa et al, 2019 who found that about a third of survivors presented within 3 days of the assault [26]. Children aged 5-12 years were less likely to present within 72 hours which may be attributed to fear of the perpetrator. Adults aged 25-44 years were three times more likely to present within 72 hours as they may be more aware of the risks of sexual abuse and the benefits of seeking medical attention early. For children aged 0-4 years, caregivers often notice signs indicative of abuse during the daily routine activities such as bathing or change in behavior. Survivors aged 13 - 15 years may not perceive the act as abuse being in a romantic relationship with the aggressor. Chitika et al, 2010 found that situations in which the perpetrator of sexual abuse is a close relative result in a reluctance of family members to seek medical care or press charges especially if there is financial dependence [27].

A third of survivors received a home or telephone follow-up visit within three months, consistent with findings by Choi, 2019 where only 35 % of survivors had a documented record of follow-up care within one year of the initial evaluation [28]. Many of the survivors do not come back for follow-up or are not reachable by phone [14]. Compliance with follow-up medical care is often poor among survivors of assault and reinforcing the benefits of follow-up care may improve compliance [29].

Limitations

Further analysis into the reasons for late presentation to the health facility was not possible as this was secondary data analysis. Several sections of the medical affidavits were incompletely filled and these had to be excluded from some of the analysis.

Conclusion

Our analysis of medical affidavits at Victoria Chitepo Provincial Hospital Victim Friendly Unit showed a distinct difference in the age distribution as most survivors of sexual assault were females aged 13- 15 years while the majority of male survivors were in the 5-12-year age group. Most sexual assaults were perpetrated by individuals that were known to the victim. Overall, there was no significant difference in the absolute number of sexual assault survivors presenting at the victim-friendly unit between 2019 and 2020 despite societal conditions that elevated the risk of sexual abuse due to the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown restrictions. The consequences of sexual abuse are enormous and medical care after rape is an emergency, however, access to care within 72 hours remains challenging.

Practical implications and recommendations

Policymakers need to formulate policies aimed at intensifying health promotion among children, adolescents, and youth encouraging timely reporting of sexual violence regardless of relationship with perpetrator through various mass media platforms.

Program Managers need to decentralize victim-friendly services for the management of sexual abuse survivors to satellite clinics to ensure timely receipt of treatment, prophylactic, and psychosocial support services within the recommended 72 hours.

National Stakeholders should provide opportunities for further research to determine barriers to timely reporting of sexual violence encounters and to closely track linkage to care and management along the bi-referral pathway between law enforcement agencies, social services providers, and the health facilities.

National Stakeholders may also create opportunities for both in-school and out-of-school adolescent girls and young women to be economically empowered.

Consent for publication: All authors that gave consent for publication of obtained data.

Availability of data: For any further information that might be required, the corresponding author is willing to provide the information.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding: No funding was availed for this study.

References

- Kappert I, Nord A, Ilse S (2016) Sexual violence is a global problem affecting all cultures and religions. Heinrich Böll Stiftung.

- Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R (2002) Sexual Violence: Chapter 6. In: World Report on Violence and Health. World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization, Pan American Health. (2012) Understanding and Addressing Violence against Women : Intimate Partner Violence. World Health Organization.

- World Health Organisation (2021) Violence against women prevalence estimates, 2018: global, regional and nationalprevalence estimates for intimate partner violence against women and global and regional prevalence estimates for non-partner sexual violence against women.

- The World Bank (2019) Gender-Based Violence (Violence Against Women and Girls). World Bank.

- Barth J, Bermetz L, Heim E, Trelle S, Tonia T (2013) The current prevalence of child sexual abuse worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Public Health. 58(3): 469-483.

- Mailhot Amborski A, Bussières EL, Vaillancourt-Morel MP, Joyal CC (2021) Sexual Violence Against Persons With Disabilities: A Meta-Analysis. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 1524838021995975.

- McCauley HL, Coulter RWS, Bogen K, Rothman EF (2018) Sexual Assault Risk and Prevention Among Sexual and Gender Minority Populations: Chapter 14. In: Sexual Assault Risk Reduction and Resistance. 333-352.

- Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency and ICF International. (2016) Zimbabwe Demographic and Health Survey 2015: Final Report.

- Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (ZIMSTAT). (2013) National Baseline Survey on Life Experiences of Adolescents, 2011.

- Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (ZIMSTAT). (2019) Zimbabwe Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2019, Snapshots of Key Findings.

- Peeters L, Vandenberghe A, Hendriks B, Gilles C, Roelens K, et al. (2019) Current care for victims of sexual violence and future sexual assault care centres in Belgium: the perspective of victims. BMC International Health and Human Rights. 19(1): 21.

- Judicial Service Commission. (2012) Protocol on the Multi- Sectoral Management of Sexual Abuse and Violence in Zimbabwe.

- Médecins Sans Frontières. Sexual and gender based violence Report: (2018) Untreated Violence: Breaking down the barriers to sexual violence care in Harare Zimbabwe 2011-2017.

- Broban A, den Bergh RV, Russell W, Benedetti G, Caluwaerts S, et al. (2020) Assault and care characteristics of victims of sexual violence in eleven Médecins Sans Frontières programs in Africa. What about men and boys? PLOS ONE. 15(8): e0237060.

- World Health Organisation. (2003) Guidelines for medico-legal care of victims of sexual violence.

- Hammond L, Ioannou M, Fewster M (2016) Perceptions of male rape and sexual assault in a male sample from the United Kingdom: Barriers to reporting and the impacts of victimization. Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offender Profiling. 14(2): 133–149.

- Byrne G (2018) Prevalence and psychological sequelae of sexual abuse among individuals with an intellectual disability: A review of the recent literature. J Intellect Disabil. 22(3): 294-310.

- Kheswa J (2014) Mentally Challenged Children in Africa: Victims of Sexual Abuse. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences. 5(27): 959-965.

- Adams JA, Farst KJ, Kellogg ND (2018) Interpretation of Medical Findings in Suspected Child Sexual Abuse: An Update for 2018. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 31(3): 225-231.

- Vrolijk-Bosschaart TF, Brilleslijper-Kater SN, Benninga MA, Lindauer RJL, Teeuw AH (2018) Clinical practice: recognizing child sexual abuse—what makes it so difficult? Eur J Pediatr. 177(9): 1343-1350.

- Cashmore J, Shackel R (2014) Gender Differences in the Context and Consequences of Child Sexual Abuse. Current Issues in Criminal Justice. 26(1): 75-104.

- Tapesana S, Chirundu D, Shambira G, Gombe NT, Juru TP, et al. (2017) Clinical care given to victims of sexual assault at Kadoma General Hospital, Zimbabwe: a secondary data analysis, 2016. BMC Infectious Diseases. 17(1): 602.

- Martin R, Ahlenback V (2020) Stopping Abuse and Female Exploitation (SAFE) Zimbabwe Technical Assistance Facility Evidence Synthesis: Secondary impacts of COVID-19 on gender- based violence (GBV) against women and girls in Zimbabwe.

- Mekaoui N, Aouragh H, Jeddi Y, Rhalem H, Dakhama BSB, et al. (2021) Child sexual abuse and COVID-19 pandemic: another side effect of lockdown in Morocco. The Pan African Medical Journal. 38: 57.

- Kufa K, Magure T, Shambira G, Gombe NT, Juru TP, et al. (2019) Utilisation of Medical Services and Outcomes at Adult Rape Clinic at Parirenyatwa Group of Hospitals, Zimbabwe. African journal of reproductive health. 23(4): 99-107.

- Chitereka C (2010) Child Sexual Abuse in Zimbabwe. Asia Pacific Journal of Social Work and Development - ASIA PAC J SOC WORK DEV. 20(1): 29-40.

- Choi ES (2019) The Care of The Sexual Assault Patient. Yale Medicine Thesis Digital Library.

- Carol K Bates CK, Moreira ME, Grayzel J (2019) Evaluation and management of adult and adolescent sexual assault victims.