L.S.M. Sigera1, P.G.R.U.M. Welagedara1, M.K.H. Madhushika1, K.M.T. Bandara2, S.V. Mendis3, D. Weerasekera4, N.S. Chandrasiri2, P.I. Jayasekera1

1Department of Mycology, Medical Research Institute, Colombo 08

2 Department of Microbiology, Colombo South Teaching Hospital, Kalubowila

3Department of Medicine, Colombo South Teaching Hospital, Kalubowila

4Department of Surgery, Colombo South Teaching Hospital, Kalubowila

*Corresponding Author: P.G.R.U.M. Welagedara, Department of Mycology, Medical Research Institute, Colombo 08.

Abstract

Candida auris is a novel yeast causing invasive infections with significant mortality around the world. Diagnosis of this organism would be difficult due to frequent misidentification by conventional methods. Multidrug resistant nature of C. auris has made the management further complicated specially in low middle income countries (LMIC). Rapid diagnosis, proper management including infection control measures are vital in these infections to prevent outbreaks due to its high transmissibility reported among patients.

Introduction

C. auris is an emerging fungal pathogen causing invasive infections leading to significant mortality due to its multidrug resistant property. It has not been identified in Sri Lanka before, due to unavailability of advanced diagnostic methods.

C. auris could be commonly misidentified as other Candida species such as C. haemulonii or C. famata by using phenotypic characteristics and biochemical testing in conventional laboratories where molecular diagnostics are needed for the accurate diagnosis. This case highlights the challenges encounter by LMIC like Sri Lanka in managing C. auris infections due to limited resources.

Case History

Sixty-eight-year-old male patient who was a known diabetic admitted to emergency treatment unit of a Teaching Hospital due to drowsiness for 3 hours duration. He was recently managed for a badly infected lower limb wound which has ultimately resulted in above knee amputation (AKA) a week before this admission.

On admission Glasgo-Coma Scale (GCS) was 6/15 but was afebrile. He was tachycardic (145 beats per minute) and tachypneic (30 breaths per minute) with 93% of oxygen saturation on air. ECG was normal and found to have high blood sugar index.

He was haemodynamically stable, and intravenous (IV) insulin and IV fluids were started to manage possible hyperglycemic hyperosmolar state.

He was transferred to the medical ward for further management. Blood and urine cultures were obtained and IV ceftriaxone 1g 12 hourly and oral metronidazole 400 mg 8 hourly were started. Since AKA stump was unhealthy IV flucloxacillin 500 mg 8 hourly was also added and wound debridement was done.

On admission his white blood cell count (WBC) was 14.7 x 109 /L, C-reactive protein (CRP) was 81 mg/L, serum creatinine (SCr) was 118 µmol/L, alanine transaminase and aspartate transaminase (ALT/AST) were 64/91 IU/L and total bilirubin was 7.54 µmol/L. Urine full report (UFR) revealed moderately field full pus cells. Blood and urine cultures became positive for Candida species on day 4 of admission and IV fluconazole 400 mg daily was started following a loading dose of 800 mg on day 1. A repeat blood culture was planned to be done after 48 hours of antifungals and the patient was transferred to the surgical ward for the stump wound management. On day 8, IV ceftriaxone and flucloxacillin were omitted and IV piperacillin-tazobactum 4.5g 8 hourly was started due to poor clinical response. IV fluconazole was continued. Patient’s GCS was fluctuating between 9/15 to 13/15. On day 9 patient developed high fever spikes with low blood pressure and reduced oxygen saturation. GCS was 8/15 and aspiration pneumonia was also suspected. IV noradrenalin was started to stabilize the blood pressure. WBC was 7 x 109 /L, CRP was rising (128 mg/L), SCr 118 µmol/L, ALT/AST were 61/88 with total bilirubin 2.9 µmol/L. Next day patient went into cardiorespiratory arrest and despite resuscitation patient expired on the same day.

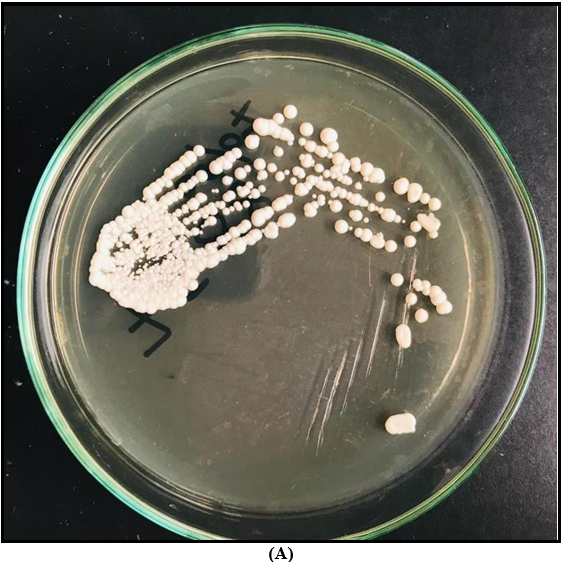

The Candida species isolated from blood culture was sent to Department of Mycology at Medical Research Institute (MRI) Colombo which is the Mycology Reference Laboratory in Sri Lanka. Since the identification was not possible from routine phenotypic and biochemical methods further identification methods were followed.

The isolate tolerated 42 ℃ temperature and grew on 10% NaCl medium. Therefore, it was sent for sequencing to a private sector laboratory as facilities were lacking in government sector.

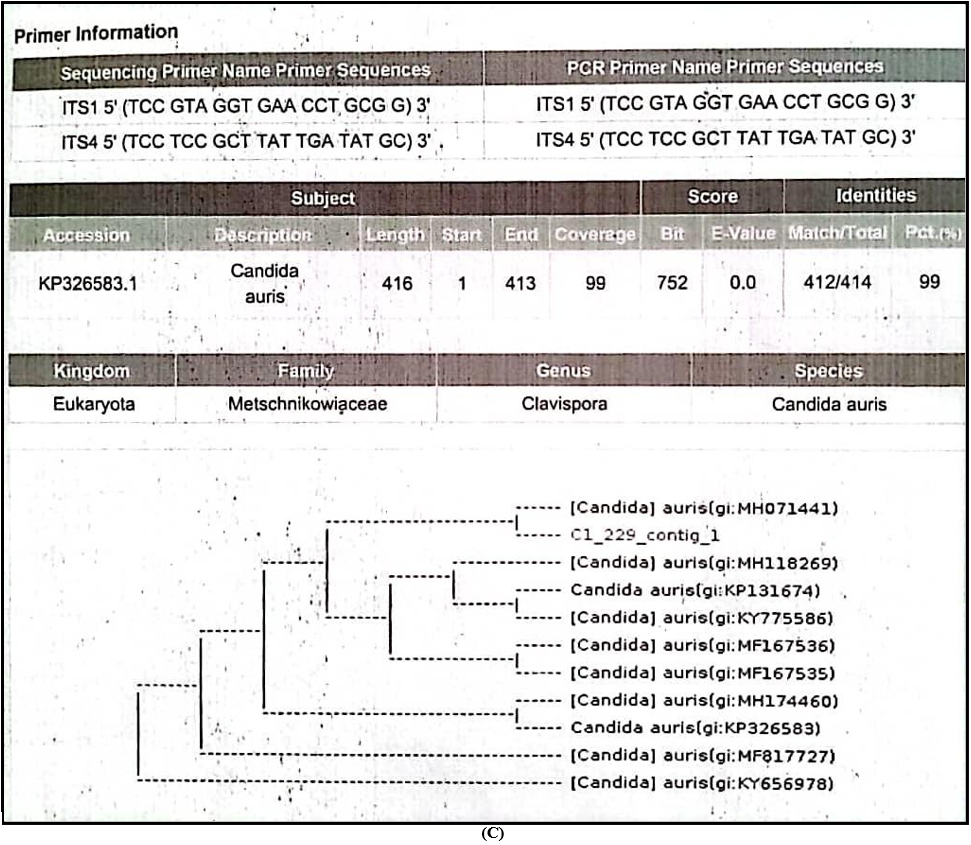

Sequencing of Internal Transcribed Spacer [ITS-1 5’(TCC GTA GGT GAA CCT GCG G)3’and ITS-4 5’(TCC TCC GCT TAT TGA TAT GC)3’ ] regions were performed and finally it was identified as Candida auris (Family-Metschnikowiaceae, Genus- Clavispora) for the 1st time in Sri Lanka.

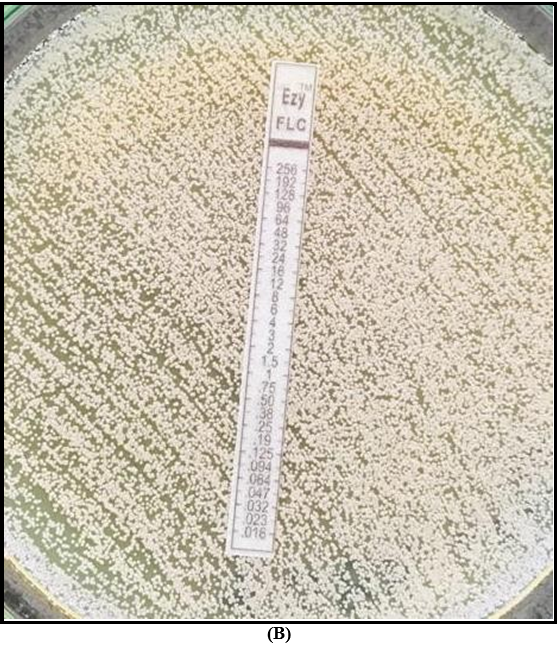

Antifungal susceptibility testing (AFST) was performed with E strips on RPMI (Roswell Park Memorial Institute) agar, and the MIC was ≥32 for fluconazole and 1.5 for amphotericin B.

Unfortunately, the correct identification was made about 2 months after the index case was managed due to the unavailability of resources in Sri Lanka.

A – Colony appearance on Sabouraud Dextrose Agar (SDA); White colour, smooth, glistening butyrous colonies

B – AFST on RPMI agar showing resistance to fluconazole

C – Results of DNA sequencing

Discussion

C. auris is a novel yeast which was first identified in Japan in 2009 from a patient with external ear discharge [1]. It is now considered as an emerging multidrug-resistant pathogen which can cause invasive infections with high mortality.

Lockhart et al. analyzed C. auris isolates from India, Pakistan, Venezuela and South Africa in 2017 and confirmed the simultaneous and independent emergence of different clonal populations of multidrug-resistant C. auris on 3 continents by analyzing whole genome sequencing [2].

It has been reported in more than 20 countries on five continents now [3]. But this is the 1st reported case of C. auris from Sri Lanka. Infections due to C. auris is a global health threat due to many reasons. Multidrug resistant nature, difficulty in diagnosis and high transmissibility of the organism in health care setting are some of them [3]. Therefore, C. auris is named under the critical category in the fungal priority pathogen list developed by WHO (WHO FPPL) in 2022 [4].

The patient described here is a 68-year-old male with poorly controlled diabetes with recent past history of AKA. Since both blood and urine cultures were positive for Candida it was likely that this patient was having urosepsis due to C. auris. Due to resource limitation only blood culture isolate was speciated using sequencing. This is a probable nosocomial infection acquired during previous hospitalization for above knee amputation. Though he had an unhealthy stump wound, it is difficult to interpret its association towards his outcome since a tissue diagnosis was not made.

Although Candida albicans is the commonly reported species from urinary isolates, C. auris also has been identified as a cause of urinary tract infection throughout the world [5]. Although there are reported cases of C. auris urinary colonization resulting in candidaemia in different countries, C. auris related urosepsis is less reported [5,6].

Since the identification was not available at the time of management of this patient, he was treated with IV fluconazole to which the isolate showed resistance later. Though an echinocandin is generally considered as the drug of choice for candidaemia in critically ill patients, IV fluconazole was used instead since echinocandin is not widely available in the country [7].

For the accurate identification of C. auris it is recommended to use molecular methods based on DNA sequencing or mass spectrometry which are not freely accessible in Sri Lanka [3].

Multidrug resistance is a well-recognized feature of C. auris which has resulted in limited treatment options. Centre for Disease Control (CDC) has proposed tentative breakpoints for C. auris depending on other Candida sp. since MIC break points are not well established. Tentative break points are ≥32 for fluconazole, ≥2 for amphotericin B or ≥1.5 if using E test, ≥4 for anidulafungin and micafungin, and ≥2 for caspofungin [3]. According to these break points both fluconazole and amphotericin B were resistant in this case and facilities were not available to assess echinocandin susceptibility.

Unfortunately, our patient expired on day 10 of admission while on treatment with fluconazole to which the isolate was resistant. Persistence of candidaemia must have resulted in his deterioration though it was not evaluated in this case properly by a repeat blood culture while on antifungal treatment.

This case highlights the importance of speciation of Candida sp. specially the invasive isolates from sterile sites. Because different species have characteristic antifungal resistant patterns, speciation would aid clinicians to decide on appropriate antifungal therapy [3].

Species identification is not only important for antifungal therapy but also needed to commence infection control measures in C. auris infections. There are increasing evidence for persistent colonization of C. auris in hospital environments as well as on different body sites of patients resulting high transmission and outbreaks in healthcare settings. Recent studies have shown that C. auris can persist on skin and other body sites as colonizers even after months following initial infection posing a major risk to other patients [8].

Therefore, it is necessary to follow strict transmission based precautions when C. auris is isolated from invasive infections as well as from non-sterile sites as a colonizer to prevent transmission to other patients. [3,9].

It is recommended to isolate the patient as well as their contacts, use of personal protective equipment by healthcare workers when handling these patients, screening of other patients in affected wards, use of chlorhexidine to decontaminate skin, cleaning of the environment with chlorine-based reagents and terminal cleaning with ultraviolet (UV) light or with hydrogen peroxide vapor for the effective control of this pathogen with high transmissibility [8].

Due to delayed diagnosis, it was not possible to impose adequate infection control measures to prevent its transmission in the hospital. At the same time most of the LMIC like Sri Lanka do not have single room isolation facilities in majority of government hospitals limiting the implementation of adequate infection control measures on time. According to available data echinocandin is recommended as first line empiric therapy where amphotericin B has been recommended as an alternative option for patients with poor response to echinocandins. Antifungal susceptibility testing is recommended in C. auris infections and close monitoring of patients while on treatment is important to detect treatment failures due to acquired resistance during therapy [3,10]. Synergism has been detected in combination of micafungin and voriconazole favoring the treatment of multidrug resistant C. auris isolates [11].

However, echinocandin may not be the choice of treatment when it comes to urinary tract infections as in this case. Echinocandins are poorly concentrated in urine so less useful for treatment of urinary tract infections due to resistant Candida species. Combination therapy with amphotericin and flucytosine has been recommended in these instances [11]. But most of these drugs are not widely available in LMIC like Sri Lanka. Therefore, it will be a great challenge for clinicians to manage C. auris infections in Sri Lanka, though its existence in the country was confirmed by this case.

Conclusion

C. auris is a novel multidrug resistant yeast causing invasive infections and it has been reported across the globe. Since it requires sophisticated diagnostic modalities, most of the time they are misidentified as other Candida species with conventional methods. Echinocandins are considered as the drug of choice in most of C. auris infections but they are not widely available in LMIC. Though early diagnosis and appropriate antifungal therapy are needed to reduce mortality in C. auris infections, it is really difficult to optimize such patients in a country like Sri Lanka due to limited facilities.

References

- Kordalewska M, Zhao Y, Lockhart SR, Chowdhary A, Berrio I, et al. (2017) Rapid and Accurate Molecular Identification of the Emerging Multidrug-Resistant Pathogen Candida auris. Diekema DJ, editor. J Clin Microbiol. 55(8): 2445–2452.

- Lockhart SR, Etienne KA, Vallabhaneni S, Farooqi J, Chowdhary A, et al. (2017) Simultaneous Emergence of Multidrug-Resistant Candida auris on 3 Continents Confirmed by Whole-Genome Sequencing and Epidemiological Analyses. CLINID. 64(2): 134– 140.

- Forsberg K, Woodworth K, Walters M, Berkow EL, Jackson B, et al. (2019) Candida auris : The recent emergence of a multidrug- resistant fungal pathogen. Medical Mycology. 57(1): 1–12.

- WHO (2022) WHO fungal priority pathogens list to guide research, development and public health action. Report.

- Griffith N, Danziger L (2020) Candida auris Urinary Tract Infections and Possible Treatment. Antibiotics. 9(12): 898.

- Biagi MJ, Wiederhold NP, Gibas C, Wickes BL, Lozano V, et al. (2019) Development of High-Level Echinocandin Resistance in a Patient With Recurrent Candida auris Candidemia Secondary to Chronic Candiduria. Open Forum Infectious Diseases. 6(7): ofz262.

- Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes DR, Clancy CJ, Marr KA, et al. (2016) Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Candidiasis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 62(4): e1–e50.

- Chowdhary A, Sharma C, Meis JF (2017) Candida auris: A rapidly emerging cause of hospital-acquired multidrug-resistant fungal infections globally. Hogan DA, editor. PLoS Pathog. 13(5): e1006290.

- Sigera L, Jayawardena M, Thabrew H, Jayasekera P (2020) Candida auris: A brief review. Sri Lankan J Infec Dis. 10(1): 2.

- Cortegiani A, Misseri G, Giarratano A, Bassetti M, Eyre D (2019) The global challenge of Candida auris in the intensive care unit. Crit Care. 23(1): 150.

- Jeffery-Smith A, Taori SK, Schelenz S, Jeffery K, Johnson EM, et al. (2018) Candida auris: a Review of the Literature. Clin Microbiol Rev. 31(1).