Carlos Andrés Arroba López1, Diego Cadena-Aguirre2*, Lenin Paul Bonifaz Manzano3, Renzo Turcato1, Nicanor Reategui1

1Department of General Surgery, Clínica Santa Clara de Quilmes, Buenos Aires, Argentina.

2Department of General Surgery, Hospital Metropolitano de Quito, Quito, Ecuador.

3PGY3 School of Medicine, Universidad de las Américas (UDLA), Quito, Ecuador.

*Corresponding Author: Diego Cadena-Aguirre, Department of General Surgery, Hospital Metropolitano de Quito, Quito, Ecuador.

Abstract

Blunt neck trauma is an uncommon but potentially fatal condition due to the presence of vital structures in the cervical region. Combined tracheoesophageal injury exceptionally rare and presents a significant diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. We report the case of a 34-year-old male who sustained blunt neck trauma following a motorcycle accident. Upon arrival, he presented with dyspnea, subcutaneous emphysema, pneumothorax, necessitating urgent airway management. Surgical exploration tracheoesophageal transection. He underwent tracheal and esophageal end-to-end anastomosis, distal tracheostomy and gastrostomy placement. Postoperative recovery was uneventful, and he was discharged on postoperative day 15. Early diagnosis and timely surgical intervention are crucial to reduce morbidity such as tracheal stenosis, tracheoesophageal fistulas, and mortality. The role of postoperative cervical immobilization and prolonged tracheostomy remains controversial. Nutritional support via gastrostomy or jejunostomy is essential in severe esophageal injuries This case highlights the importance of a multidisciplinary approach in managing complex cervical trauma. Establishing clear diagnostic and treatment protocols is crucial to improving patient prognosis.

Keywords: Blunt neck trauma, tracheoesophageal transection, tracheal trauma, esophageal trauma.

Introduction

Trauma is one of the leading causes of mortality worldwide, representing a major public health concern with a significant impact across all age groups. It is estimated that traumatic injuries account for approximately 8% of global deaths, with a substantial proportion occurring in young patients [1]. Neck trauma can result from motor vehicle accidents, assaults, or sports-related injuries, exhibiting a wide range of severity [2].

Blunt trauma occurs due to compression, acceleration-deceleration forces, or a combination of these mechanisms [3]. In compression injuries, an external force acts against a fixed object, causing deformation of a hollow organ and increased intraluminal pressure until the tensile strength of the tissue is exceeded, leading to rupture [4]. Acceleration-deceleration forces cause abrupt stretching and shearing at the interface between fixed and mobile structures, potentially disrupting organs, connective tissue, blood vessels, and nerves [4].

Blunt neck trauma is a rare but potentially fatal condition due to the complex anatomy of the region, where vital structures such as the trachea, esophagus, blood vessels, and cervical spine may be compromised. Combined tracheal and esophageal injury is extremely rare, with an incidence of less than 1% in trauma centers and a high mortality rate at the scene of the accident [5].

In Argentina, the National Road Safety Agency (ANSV) estimated that 32% of the national budget allocated to road traffic accidents was spent on motorcyclists with head and neck trauma (including traumatic brain injury), posing a significant challenge due to limited public resources and the need for effective prevention policies [6].

Clinical manifestations of tracheal trauma include dyspnea, stridor, hemoptysis, and subcutaneous emphysema, whereas esophageal injury may present with dysphagia, sialorrhea, cervical pain, and signs of pneumomediastinum or pneumothorax [7].

The management of cervical trauma varies depending on the affected zone, hemodynamic stability, and clinical findings. These findings are classified into hard signs, such as active pulsatile bleeding, expanding hematoma, absence of carotid pulse, vascular bruit or thrill, and cerebral ischemia, and soft signs, including a history of bleeding at the trauma site, vascular territory injury, and small non-pulsatile hematomas. In cases of major signs, after following ATLS protocols for initial stabilization and hemorrhage control, surgical exploration is mandatory [8].

If hemodynamic stability is maintained and no major warning signs are present, diagnosis requires a combination of clinical evaluation and imaging studies, such as computed tomography (CT), which provides high sensitivity and specificity (90-100%) in identifying vascular and soft tissue injuries [8]. Additional studies, such as bronchoscopy and endoscopy, are useful in cases of subcutaneous emphysema, pneumomediastinum, or pneumothorax without clear identification of a hollow viscus injury on CT [8].

Initial management is based on securing the airway and providing hemodynamic support, followed by early surgical repair to minimize complications. Surgical options for cervical tracheal avulsion include primary anastomosis with the interposition of muscle flaps in extensive or contaminated defects. Distal tracheostomy ensures airway patency until tracheal healing is achieved. There is no consensus regarding the need for chin-to-chest sutures to prevent extension during the recovery period, although it may be considered in cases where devitalized tracheal tissue has been resected to reduce postoperative tension and ischemia [8-10].

For cervical esophageal avulsion, options include end-to-end anastomosis or esophageal diversion in complex cases. Esophageal reconstruction is recommended with 4-0 absorbable monofilament sutures, such as polydioxanone (PDS) or polyglycolic acid (Vicryl), to minimize inflammatory reactions. In these cases, distal enteral feeding via gastrostomy or jejunostomy is recommended, with the latter being preferred due to the potential need for a gastric tube in esophageal reconstruction [8-11].

Case Report

A 34-year-old male patient with no relevant medical history presented to the emergency department following blunt neck trauma secondary to a motor vehicle accident while riding a motorcycle without a helmet. He was transported by ambulance with immobilization measures in place, without endotracheal intubation.

Upon arrival, the patient exhibited dyspnea, tachycardia, normotension, tachypnea and neck subcutaneous emphysema. Emergency endotracheal intubation and chest tube placement were performed due to tension pneumothorax. He was immediately taken to the operating room.

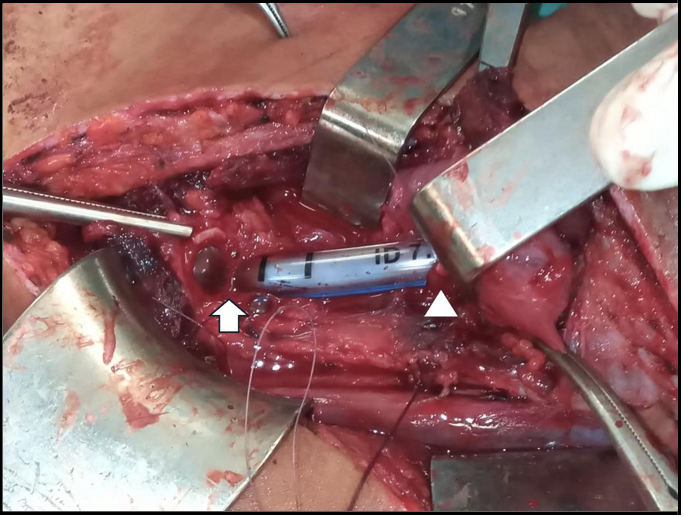

Surgical exploration via a left presternocleidomastoid incision revealed intact neurovascular bundles and a complete transection of the trachea and esophagus (Figure 1-2).

Figure 1: Tracheal avulsion. Head arrow indicates proximal segment. Arrow indicates distal segment.

Figure 2: Esophageal avulsion. Head arrow indicates proximal segment with NG tube. Arrow indicates distal segment.

A protective distal tracheostomy was performed to secure the airway (Figure 3), followed by end-to-end tracheal anastomosis. The esophageal injury was repaired with a manual end-to-end anastomosis and gastrostomy placement for enteral feeding (Figure 4) along with cervical drain placement.

Figure 3: Tracheostomy distal to avulsed trachea.

Figure 4: End-to-end tracheal anastomosis from posterior to anterior aspect

The patient remained on mechanical ventilation for the first four days in the intensive care unit. The patient was discharged on postoperative day 15 in stable condition with a tracheostomy cannula for secondary airway evaluation.

Discussion

This case highlights the rarity and complexity of blunt neck trauma with tracheoesophageal transection. The low incidence of this injury limits the accumulation of robust clinical evidence, requiring the extrapolation of management strategies from isolated experiences and general cervical trauma recommendations. Decision-making in these cases largely depends on the patient’s hemodynamic stability and access to advanced diagnostic and therapeutic resources [8].

Early identification of the injury is a major challenge. In this case, the diagnosis was confirmed through surgical exploration, underscoring the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion in patients with high-impact cervical trauma. In the absence of hemodynamic instability and hard signs, CT is the diagnostic modality of choice [8]. If the tracheal or esophageal injury is suspected but not identified on CT, bronchoscopy and endoscopy should be considered. MRI is not recommended [9].

Timely surgical treatment is crucial in reducing complications such as tracheal stenosis, tracheoesophageal fistulas, or mediastinal infections. Primary anastomosis has shown favorable functional outcomes when performed under optimal conditions, minimizing the need for subsequent reconstructive procedures. However, controversies persist regarding the prolonged use of tracheostomy and cervical immobilization strategies in the postoperative period. Some authors have suggested the use of a chin to chest stitch, also known as Guardian chin stitch, to reduce the risk of hyperextension and potential anastomotic leakage [12]. However, a series of 165 patients undergoing laryngotracheal resection without chin-to-chest suturing did not show an increased risk of anastomotic leaks, although this study did not include trauma cases [13]. Given that chin-to-chest stitch increases the risk of neurological injury, with reported cases of paraplegia and quadriplegia [13], it should be reserved for selected cases, applied with delicate flexion, and maintained for the shortest duration possible.

This case also highlights the importance of early nutritional support via gastrostomy or jejunostomy in severe esophageal injuries. The use of percutaneous or endoscopic gastrostomy has been described to avoid the need for laparotomy, although its feasibility depends on local expertise and the characteristics of the esophageal injury [14]. While muscle flaps have been used for large esophageal defects [15], there is no consensus regarding their routine use.

Finally, this case underscores the need to establish clear protocols for the diagnosis and management of tracheoesophageal trauma, aiming to improve patient prognosis and quality of life. Further research is necessary to refine repair strategies and assess long-term functional outcomes in these patients.

References

- Craig H.A, Lowe D.J, Khan A, Paton M, Gordon M.W (2024) Exploring the Impact of Traumatic Injury on Mortality: An analysis of the certified cause of death within one year of serious injury in the Scottish population. Injury. 55(6): 111470.

- Shilston J, Evans D.L, Simons A, Evans D.A (2021) Initial management of blunt and penetrating neck trauma. BJA Education. 21(9): 329–35.

- Varma D, Brown P, Clements W (2023) Importance of the Mechanism of Injury in Trauma Radiology Decision-Making. Korean Journal of Radiology. 24(6): 522–28.

- Grande C.M (1990) Mechanisms and Patterns of Injury: The Key to Anticipation in Trauma Management. Critical Care Clinics. 6(1): 25–35.

- Ebrahimian R, Moayerifar M, Gholipour M, Mohammadian M, Moayerifar M (2024) Combined tracheoesophageal transection following a life-threatening clothesline-type blunt neck trauma: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 114: 109173.

- Dirección de Investigación Accidentológica. Ministerio de Trasporte de la Argentina (2022) Costos de la atención médica del traumatismo de cabeza y cuello en motociclistas siniestrados viales de Argentina.

- Kelly J.P, Webb W.R, Moulder P.V, Moustouakas N.M, Lirtzman M (1987) Management of airway trauma. II: Combined injuries of the trachea and esophagus. Ann Thorac Surg. 43(2): 160-3.

- Qureshi M, Patel K, Simon R (2020) Neck level algorithmic approach to trauma. Operative Techniques in Otolaryngology- Head and Neck Surgery. 31(4): 289–94.

- Moonsamy P, Sachdeva U.M, Morse C.R (2018) Management of laryngotracheal trauma. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 7(2): 210-216.

- Petrone P, Velaz-Pardo L, Gendy A, Velcu Le, Brathwaite C.E.M et al. (2019) Diagnóstico, manejo y tratamiento de las lesiones cervicales traumáticas. Cirugía Española. 97(9): 489–500.

- Grabill N, Louis M, Redenius N, Cawthon M, Gibson B (2024) Blunt trauma-induced complete esophageal avulsion: A case report on surgical intervention and clinical insights. Trauma Case Reports. 54: 101117.

- Mathisen D.J, Grillo H.C (1987) Laryngotracheal Trauma. Ann Thorac Surg. 43: 254–62.

- Schweiger T, Evermann M, Roesner I, Frick A.E, Denk-Linnert D.M, et al. (2021) Laryngotracheal resection can be performed safely without a guardian Chin stitch—a single-centre experience including 165 consecutive patients. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 60(2): 402–408.

- Darlong L.M, Shunyu N.B, Das R, Mallik S (2009) Cut throat zone II neck injury and advantage of a feeding jejunostomy. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2(3): 213-5.

- Sanchez J.A, Panait L (2012) Surgical Repair of Long-Segment Cervical Esophageal Injury With a Sternocleidomastoid Myocutaneous Flap. Ann Thorac Surg. 94(1): 305–7.