Marco Antonio Stefani*, Eduarda Tanus Stefani, Mariana Tanus Stefani

Department of Neurosurgery, HospitaldeClinicasdePortoAlegre, FederalUniversityofRio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil

*Corresponding Author: Marco Antonio Stefani, Department of Neurosurgery, Hospital de Clinicas de Porto Alegre, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil

Abstract

Background and Purpose: The presence of both arterialized veins (typical of arteriovenous malformations) and classical caput medusa (characteristic of Developmental Venous Anomalies) in digital subtraction angiographies demonstrates a hybrid type of vascular malformation. It also brings the question of possible increased risk for hemorrhagic events or other neurological consequences in this subtype of venous angioma.

Methods: The authors present 3 cases of vascular malformations with mixed angiographic features evident during high-quality digital subtraction angiographies. Clinical and morphological aspects of these vascular abnormalities are discussed, considering previous reports in the literature.

Results: Two women and one man were studied with DSA due to the presence of enlarged vessels on Magnetic Resonance (MR) imaging. All of them had MR characteristics of venous angioma (caput-medusae). Presentation forms were intracerebral hemorrhage in one, seizure in the other, and one patient with migrainous type headache. The case with hemorrhage was treated with Brain Stereotactic Radiosurgery.

Conclusions: Based on the review of the literature and the present cases it is possible to identify an intermediate form of vascular malformation, between arteriovenous and venous angioma. In this condition, the chances for a hemorrhagic presentation are still unknown and might be increased and further prospective studies should be conducted to assess this risk.

Keywords: cerebrovascular disorders, vascular malformations, intracerebral hemorrhage, angiography, developmental venous anomalies

Introduction

Background and purposes

Developmental venous anomalies (DVA) are quoted as benign lesions since their initial descriptions in the literature, as they rarely present with hemorrhage or are associated with neurological morbidity [4]. However, it has been described in some cases a variation on the classical angiographic aspects - caput-medusae feature visible only on venous fase - with the presence of precocious ! arterialized" veins seen on the digital subtraction angiography(DSA). The presence of such a feature raises the question of a possible increased risk of hemorrhage and other neurological consequences.

This specific group may in fact represent a separate pathological entity and perhaps should not be classified as true venous angioma. The present work reports three cases of atypical vascular malformations with unique angiographic characteristics and raises some questions about the definition and management of this condition.

Patients and Methods

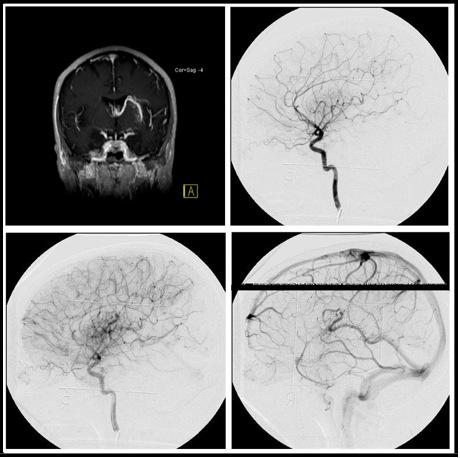

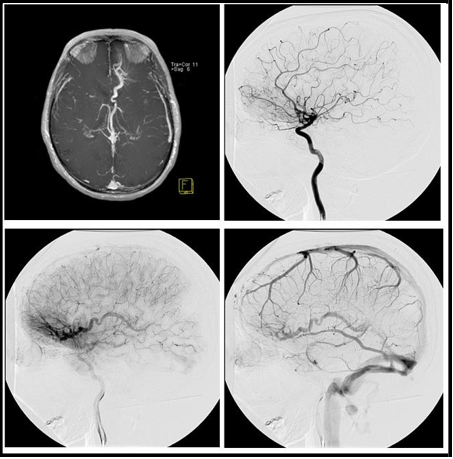

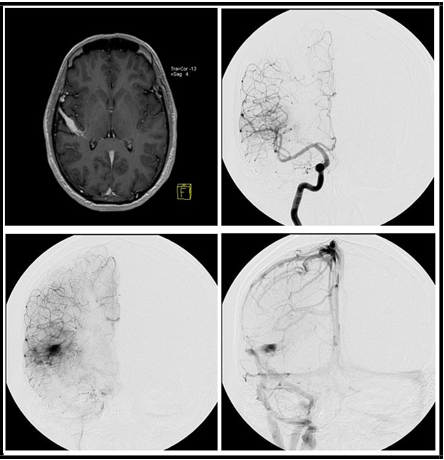

Three patients presented on this series were seen in the clinic for different reasons: One 50 years- old man was investigating recent onset of seizures, another woman aged 45 had an incidental finding during the investigation of a headache and the last one was a young woman (age 28) studied with DSA during the procedure of stereotactic radiosurgery after an episode of intracerebral hemorrhage attributed to a vascular abnormality seen on a DSA’s arterial phase. The first 2 patients were not treated for the vascular abnormality. The images seen on MR and DSA are presented in Figures 1 to 3.

Figure 1: (A) MR showing an enlarged vein with the classic pattern developmental venous anomaly (caput medusa). Lateral view sequence (B, C and D) of digital subtraction angiography demonstrating the presence of a large early draining vein, with the classical aspect of venous angioma.

Figure 2: (A) MR showing an enlarged vein with the classic pattern developmental venous anomaly (caput medusa). Lateral view sequence (B, C and D) of digital subtraction angiography demonstrating the presence of a large early draining vein, with the classical aspect of venous angioma.

Figure 3: (A) MR showing an enlarged vein with the classic pattern developmental venous anomaly (caput medusa). Frontal view sequence (B, C and D) of digital subtraction angiography demonstrating the presence of a large early draining vein, with the classical aspect of venous angioma.

Discussion

The venous angioma, also known as varix or developmental venous anomaly has the classical definition of being dilated veins with classical “caput medusae” aspect draining normal tissue, usually associated with the absence of a venous pathway that would normally draw off the territory and draining in a normal extra parenchymal collector [4,8]. It also is a common finding described on MR exams performed for neurologic investigations and has an anatomic distribution according to the transcerebral vein territory already well described elsewhere [2,10]. When a DSA is performed, this is typically found in the venous phase.

It is thought to represent a primary dysplasia of capillaries and small transcerebral veins or a compensatory mechanism caused by an intrauterine accident resulting in thrombosis of normal venous pathways.2. In one large series of 4069 consecutive brain autopsies, 105 DVAs were found, a frequency of 2.5 %, as compared with only 24 AVMs and 16 cavernous angiomas [6].

The reports of Camacho et al and Rulz et al call attention to the fact that in about 60 % of the cases DVA comes together with other cerebral parenchymal abnormalities such as cortical hypoplasia, calcifications, density or signal abnormalities, cavernous malformations, and modified perfusion patterns at M R [1,10].

Based on the few classical studies of natural history they are usually quoted as innocent incidental, as they rarely bleed or present with symptoms [3,5,7]. Due to these assumptions, the current practice for DVA is conservative management without specific treatment targeting the vascular lesion.

However, there is a different subgroup of vascular venous abnormalities described as mixed cerebrovascular malformation in which a DVA coexists with micro arteriovenous malformation [9]. These were also called arterialized DVA on a recent series, with cases similar to those presented in the current study. After an extensive review of the literature, these authors found 53 cases, with the hemorrhagic presentation in one-third of the cases and is coincidental with the present series.

As it can be observed on the images, the angiographic aspects of this particular group are confusing. Classical features of venous angioma such as caput medusa and dilated veins are present and certainly would be considered benign lesions if present only late in the venous phase of the angiography. However, the early draining vein found on each exam is visible and immediately raises the concern of a potential risk of hemorrhage or other neurological complications.

Angiographic features, even found in cases with the hemorrhagic presentation, are not necessarily predictors of hemorrhagic risk, and only natural history studies can be used to draw associations with clinical outcomes [11,12]. As in AVM literature, it is not possible to simply extrapolate the angiographic characteristics as determinants of risk for future bleeding, they reflect only features present in one moment of the DVAs natural history and provide unclear information in terms of outcome. The influence of these factors present at the first presentation on the clinical course requires prospective follow-up to assess.

If considered as a different subtype of DVA (with different natural history), then incidental MR enlarged veins should be looked closer, with different imaging protocols and DSA to detect potential arterialized components. In this situation, it could be possible to justify a prophylactic treatment to avoid hemorrhagic outcomes. If in contrast, they continue to be in the classical group of DVA, physicians will rely on natural history studies of DVA to give patients the reassurance of low risk of future bleeding.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Camacho DLA, Smith JK, Grimme JD, Keyserling HF, Castillo M (2004) Atypical MR Imaging Perfusion in Developmental Venous Anomalies. AJNR: American Journal of Neuroradiology 25(9): 1549-52.

- Goulao A, Alvarez H, Monaco RG, Pruvost P, Lasjaunias P (1990) Venous anomalies and abnormalities of the posterior fossa. Neuroradiology. 31(6): 476–482.

- Kurt G, Aslan A, Kara E, Erol G, Şahin MB, et al. (2021) Different Aspects on Clinical Presentation of Developmental Venous Anomalies: Are They as Benign as Known? A Single Center Experience. Clinical neurology and neurosurgery. 201.

- Lasjaunias P, Terbrugge K, Rodesch G, Willinsky R, Burrows P, et al. (1989) [True and false cerebral venous malformations. Venous pseudo- angiomas and cavernous hemangiomas]. Neuro-Chirurgie. 35(2): 132–139

- Li X, Wang Y, Chen W, Wang W, Chen K, et al. (2016) Intracerebral hemorrhage due to developmental venous anomalies. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 26: 95–100.

- McCormick WF (1966) The pathology of vascular (“arteriovenous”) malformations. Journal of neurosurgery. 24: 807–816.

- McLaughlin MR, Kondziolka D, Flickinger JC, Lunsford S, Lunsford LD (1998) The prospective natural history of cerebral venous malformations. Neurosurgery. 43(2): 195–200.

- Mooney MA, Zabramski JM (2017) Developmental venous anomalies. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 143: 279–282.

- Oran I, Kiroglu Y, Yurt A, Ozer FD, Acar F, et al. (2009) Developmental venous anomaly (DVA) with arterial component: a rare cause of intracranial haemorrhage. Neuroradiology. 51(1): 25–32.

- San Millán Ruíz D, Delavelle J, Yilmaz H, Gailloud P, Piovan E, et al. (2007) Parenchymal abnormalities associated with developmental venous anomalies. Neuroradiology. 49(12): 987–995.

- Stefani MA, Porter PJ, terBrugge KG, Montanera W, Willinsky RA, et al. (2002) Angioarchitectural factors present in brain arteriovenous malformations associated with hemorrhagic presentation. Stroke 33(4): 920–924.

- Stefani MA, Porter PJ, TerBrugge KG, Montanera W, Willinsky RA, et al. (2002) Large and deep brain arteriovenous malformations are associated with risk of future hemorrhage. Stroke. 33(5): 1220–1224.