Kedibonye Tsaone Mmachere Mareka1*, Patience N. Erick2, Amitabye Luximon-Ramma3

1School of Public Health, Texila American University, Guyana

2University of Botswana, Department of Environmental Health, Faculty of Health Sciences.

3School of Health Sciences, University of Technology, Mauritius, Mauritius

*Corresponding Author: Kedibonye Tsaone Mmachere Mareka, School of Public Health, Texila American University, Guyana.

Abstract

Prediction and prevention of unintentional injuries can protect children from unintentional injuries in child care settings. In such settings, children are more vulnerable to unintentional injuries such as falls, injuries caused by sharp objects, poisoning, burns, and shocks. This is due to their physical, psychological, and behavioral characteristics which greatly increase their vulnerability and dependence on other people for safety against unintentional injuries. Most occur at schools and daycare centers. Concurrent and retrospective designs were used to conduct a systematic review of the literature to assess the evidence of unintentional injuries available in Mogoditshane/Thamaga Subdistrict, Botswana.

A descriptive purposive sampling technique was the main technique used to select the n (52) daycare centers out of the N (61) in the previously mentioned district of Botswana. Both quantitative (Structured) and qualitative (unstructured approaches for the collection of data were utilized. Data collection was mainly through conducting interviews; administering questionnaires, rating according to the checklist, and conducting inventory audit interviews and questionnaires. The collected data were subjected to different statistical tests to answer the hypotheses of the research study. The demographics and outcome variables were summarized as mean (standard deviation) for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables such as age.

The Chi-square test was used to determine the test of association between the categorical variables. The p<0.005 was set to be significant. Mean and median child injury rates were calculated by sex, age, and child care center. Age categories were created for ages less than 1 year to 2-year- olds and, 2.0 to 3.5, and 3.6 to 5.0 years for distributions in each category. The characteristics of reported unintentional injuries (e.g., type of injury and severity) to children, ages less than 1 year to 2-year-olds and, 2.0 to 3.5 and 3.6 to 5.0 years, used frequency and proportions to examine the type of injury, body part injured location of injury occurrence, and severity of the injury.

Frequency distributions and measures of dispersion were also calculated for each of the variables such as the characteristics (e.g., educational attainment of child care providers, the ratio of child care providers to children, and age of children in unintentionally injured child’s classrooms) of the ecological context of daycare centers that may be related to the child’s development and the occurrence of unintentional injuries in children ages less than 1 year to 2-year-olds and, 2.0 to 3.5 and 3.6 to 5.0 years old in daycare centers. Child care providers for each child care center participating in the study were asked a series of questions related to their educational backgrounds, knowledge of the child, and work environment. For the subset of children ages less than 1 year to 2-year-olds and, 2.0 to 3.5 and 3.6 to 5.0 years of age who had a reported unintentional injury while at a daycare center, the answers to these questions were evaluated for descriptive statistics, including frequency and proportions, to determine components of the ecological environment of the daycare center that relate to the child’s development and unintentional injury occurrence.

The results show significant differences between injury rates for unintentional injuries among younger preschool children aged less than 2 to 3.5 than children aged 3.5 to 5 years, injury rates for unintentional injuries among boys than girls, socio-demographic factors (gender, age distribution), and time factor (peak hour for injury, peak day for injury, peak season for injury) and the occurrence of unintentional injuries in daycare centers in Mogoditshane/Thamaga Subdistrict, Botswana.

Although some efforts have been made to the prevention of unintentional injuries at the district level, more work needs to be done. The child care centers need to be actively involved in the prevention of unintentional injuries, and other critical issues about interventions that include safety policies and practices to be addressed.

Keywords: unintentional injuries, unintentional injuries prevention, the prevalence of unintentional injuries in childcare settings, contributing factors to unintentional injuries, interventions on unintentional injury prevention, day care centers / pre- schools/ preprimary units.

Introduction

Daycare centers and preschools provide custodial, educational, or developmental services to preschool-age children to prepare them to enter elementary school grades. This includes nursery schools, kindergartens, head start programs, and any similar facility primarily engaged in the care and protection of preschool-age children [1].

In such settings, children are more prone to unintentional injuries because children’s participation in such childcare settings involves constant physical activity, open-air play, and relaxation as they play around at centers. Most occur at schools and daycare centers [55]. When children are under care in a childcare setting, a child is likely not the only child there, it can be difficult for childcare providers to pay attention to every child at all times, which can lead to unintentional injuries. Unintentional injuries in childcare settings are so devastating because of the impairment that the injuries can cause to a child and the lasting impact on all aspects of the life of the child [24].

Botswana is divided into 10 districts. These are administered by local authorities (district councils, city councils, or town councils). Children's centers/childcare settings are established in the various districts of Botswana to provide a range of services including early education, social care, and health to preschool children and their families. The Kweneng district is one of the ten districts of Botswana which is of interest to the current research because of its population growth trends, projections, and prospects. The growth of its population can be seen as having a positive effect on business in the district in particular retail and other activities such as daycare centers/childcare settings to provide a range of services including retailing, early education, social care, and health to pre-school children and their families and many more.

The districts of Botswana have been further subdivided into sub-districts. Of the various subdistricts, Mogoditshane/Thamaga Subdistrict was chosen as the area of study.

Table 1: Community Development Office (S&CD in identified N(61) licensed day care centers.

|

Mogoditshane |

Thamaga |

Mmopane |

Metsimotlhabe |

Tloaneng |

Gabane |

Kumakwane |

|

33 |

13 |

6 |

4 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

Mogoditshane has the highest number of licensed daycare centers as can be seen from the table1 above. However, activities in day-care centres that are undertaken to prevent unintentional injuries in the under-fives across Mogoditshane/Thamaga Subdistrict, Botswana are not known.

“Unintentional injuries are those injuries that are not inflicted purposely, occur without the intent of harm” [16,28].

There has been little work in the district exploring childcare settings' experiences of unintentional injuries in childcare settings. If unintentional injuries cannot be addressed, the cases are likely to escalate and as a result, unnecessary lives will be lost to largely preventable causes.

A study cited that the rate of unintentional injuries for children in sub-Saharan Africa has reached 53.1 per 100,000, the highest for regions across all income levels. Despite the high burden, child injury prevention and control programs and policies are limited or non-existent in many countries in the region. Accurate data regarding these injuries across and within countries is incomplete. Population-based estimates and investigations into context-specific risk factors, safety attitudes, and behaviors are needed to inform the development of effective interventions [36]. Such kind of information would serve as the basis for child unintentional injury prevention control measures.

The study conducted a systematic review of the literature to assess the evidence of unintentional injuries available, describe the pattern of unintentional injuries examine environmental and child factors contributing to injuries and injury severity, and finally explore the activities being undertaken in daycare centers among preschool-aged children of Mogoditshane/Thamaga Subdistrict, Botswana.

Methods

Study Design

This study is a descriptive cross-sectional study design. For this type of study, the study design is used to gather data through interviews, questionnaires, and focus groups over a certain period in time which may be in the past or the present, and then analyse the results. The study design is also used to assess the prevalence of unintentional injuries in childcare settings at a specific period. We can measure factors influencing unintentional injuries and use data obtained for designing unintentional prevention programs. Concurrent and retrospective designs were also used to conduct a systematic review of the literature to assess the evidence of unintentional injuries available in the district daycare centers. A descriptive purposive sampling technique was the main technique used to select the 52 daycare centers out of the 61 in the aforesaid district of Botswana. Both quantitative (Structured) and qualitative (unstructured approaches for the collection of data were utilized.

The study population consisted of the 61 licensed daycare centers in Mogoditshane/Thamaga Subdistrict are the study day care centers identified.

Description of the Study Area

The study day care centers were described according to the villages as shown below:

|

Mogoditshane |

Thamaga |

Mmopane |

Metsimotlhabe |

Tloaneng |

Gabane |

Kumakwane |

|

|

33 |

13 |

6 |

4 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

N(61) |

Inclusion Criteria: The Day care centers were Botswana Qualification Authority accredited (BQA), public, private and nonprofit settings such as day care centers, pre-schools, play-schools, kindergartens, reception schools, crèches and nurseries, etc

Exclusion Criteria: Day Care Centers offering childcare and baby-sitting services without the approval of Mogoditshane/Thamaga subdistrict council.

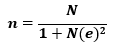

Sample Size

Sample Size Determination

The sample of the day care centers was calculated using Yamane formula with 95% confidence level [52]. The formula provided a simplified formula to calculate sample size.

Where n= sample size, N= population size and e= Margin of error (0.05)

Zone 1: Mogoditshane with 33 day centers a convenient number of 24 shall randomly be chosen from this zone below:

Zone 1: Number of licensed day care centers selected in Mogoditshane n (24)

|

Nkoyaphiri |

Ledumadumane |

Tsolamosese |

Lesirane |

Block 9 & Block 7 |

Goo Moloi |

Kgateng |

Smorden |

Maulane |

Diagane |

|

5=(3) |

10=(5) |

4=(3) |

2 |

4= (3) +1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

Zone 2- Licensed day care centers in Thamaga n(13)

|

Matsila |

Kgopa |

Mashadi Ward |

Morepo |

Sanyane |

Kontle |

Kerane |

Rungwana |

Ga-Sau |

Motlhabane |

|

3 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

The day care centers were randomly chosen from the following zone for data collection shown below:

|

Zone 3 |

Zone 4 |

Zone 5 |

Zone 6 |

Zone 7 |

|

|

Mmopane |

Metsimotlhabe |

Tloaneng |

Gabane |

Kumakwane |

|

|

6 |

4 |

1 |

3 |

1 |

n(15) |

Other participants of the study were policy Makers who included the social and Community Development Office (S&CD) in Mogoditshane/Thamaga Sub District, and the Ministry of Local government and Rural Development (1). Key informants, consisting of service providers- 1 per each childcare center 1 (52) who were SHE- 1 per each childcare center 1 (52), teachers- 1 per each childcare centre 1 (52), selected daycare centers to head -1 per each childcare centre 1 (52). Stakeholders included regulatory authorities within the Ministry of Local government and Rural Development (1).

Variables needed

Independent variables were factors contributing to unintentional injuries that were investigated in Day care centers of Mogoditshane/Thamaga Subdistrict, Botswana.

Dependent variables are Day care centers in Mogoditshane/Thamaga Subdistrict, Botswana. 61 licensed day care centers in Mogoditshane/Thamaga Subdistrict were the study day care centers identified.

A sample of the Day care centers (52) was randomly chosen from the list of 61 daycare centers.

Data collection used the self-developed five (5) survey instruments as follows:

The five survey instrument self-developed tools were used to collect data as follows:

Tool 1: Audit of case records on unintentional injuries in a daycare centre

Tool 2: Interview schedule for service providers in a daycare centre Tool 3: Interview schedule for a head of daycare centre

Tool 4: Checklist on compliance with safety standards and guidelines for licensed daycare centers.

Tool 5: Interview schedule with social services on monitoring compliance and enforcement offenses and good regulatory practices by child day care centers. Data collection was collected through conducting interviews, administering questionnaires, rating according to the checklist, and conducting an inventory audit.

The analysis of the study will look into the demographics and outcome variables summarized using descriptive summary measures expressed as mean (standard deviation) for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables such as age Chi-square test shall use to determine the test of association between the categorical variables. The p < 0.005 was set to be significant.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize important features of numerical data. Mean and median child injury rates were calculated by sex, age, and child care center. Age categories were created for ages less than 1 year to 2-year-olds and, 2.0 to 3.5, and 3.6 to 5.0 years for distributions in each category. The characteristics of reported unintentional injuries (e.g., type of injury and severity) to children, ages less than 1 year to 2-year-olds and, 2.0 to 3.5 and 3.6 to 5.0 years, in the childcare setting and other settings were analyzed using descriptive statistics, including frequency and proportions were used to examine the type of injury, body part injured, location of injury occurrence, and severity of the injury. Frequency distributions and measures of dispersion were calculated for each of the variables.

The characteristics (e.g., educational attainment of childcare providers, the ratio of childcare providers to children, and age of children in unintentionally injured child’s classrooms) of the ecological context of daycare centers may be related to the child’s development and the occurrence of unintentional injuries in children ages less than 1 year to 2-year-olds and, 2.0 to 3.5 and 3.6 to 5.0 years old in daycare centers. Childcare providers participating in the study were asked a series of questions related to their educational backgrounds, knowledge of the child, and work environment. For the subset of children ages less than 1 year to 2-year-olds and, 2.0 to 3.5 and 3.6 to 5.0 years of age who had a reported unintentional injury while at a daycare center, the answers to these questions were evaluated for descriptive statistics, including frequency and proportions, to determine components of the ecological environment of the daycare center that relate to the child’s development and unintentional injury occurrence.

Frequency distributions for the time, month, type of injury, body part injured, location, activity, contributing factors, and severity of the injuries shall be calculated, and the relations between contributing factors and injury severity were analyzed by the χ2 test. Statistical significance was set at P <.05. Data shall be analyzed by the appointed Statistician using appropriate and available Statistical Software. The results of the study shall be published in due course and recommendations made accordingly. The results are going to be discussed in the sequence of the specific objectives and terms of the conclusions drawn from the research questions associated with each specific objective and the hypothesis testing of the study. Possible implications of significant findings are going to be explored in terms of study limitations. Descriptive data results from the study are going to be aligned with previous studies that described the occurrence of unintentional injuries to children in daycare centers.

Results

Of the 61 daycare centers, 52 were sampled for the study.

Hypothesis Testing

Once the null hypotheses were tested and the results of the study would show whether:

The first Hypothesis of the Research Study would show that there is a significant difference between injuries rates for unintentional injuries among younger preschool children aged less than 2 to 3.5 than children aged 3.5 to 5 years in daycare centers. Table 3. To Test Hypothesis (𝐻01), Age-adjusted injury rates shall be calculated for each daycare center. Analyses of variance were used to analyse differences across centers for age-adjusted rates and moderate to severe injury rates. Injury rates shall be calculated and compared across children aged less than 2 to 3.5 than children aged 3.5 to 5 years in daycare centers using t-tests for mean rates and rank sums for median rates. Poisson confidence intervals (CIs) shall be calculated for mean injury rates.

The second Hypothesis of the Research Study would show that there is a significant difference between injury rates for unintentional injuries among boys and girls in daycare centers. Table 4. To Test Hypothesis (𝐻02), the T-test (aka Student’s T-test) shall be used for comparing two data groups boys and girls which had different mean values. The T-test allowed us to interpret whether differences are statistically significant or merely coincidental. The results of a T-test shall be expressed in terms of probability (p-value). If the p-value is below a certain threshold, usually 0.05, then one can be very confident that the two groups, boys and girls are different and it wasn’t just a chance variation between the sample data.

The third Hypothesis of the Research Study would show that there is a significant association between socio-demographic factors (gender, age distribution) and the occurrence of unintentional injuries in daycare centers. Table 5. To Test Hypothesis (𝐻03) using the T-test, ANOVA (analysis of variance) shall be used to compare three or more groups rather than just two. The analysis of variance shall be also used to compare multiple groups concurrently to find out if a relationship exists e.g., analysing the data to find out whether different types of age and gender groups and other categorical variables get different unintentional injury responses in various settings. The Chi-square test shall be used to determine the test of association between gender and age distribution of the categorical variables. The p < 0.005 was set to be significant.

The fourth Hypothesis of the Research study would show that there is a significant association between time factors (peak hour for injury, peak day for injury, peak season for injury) and the occurrence of unintentional injuries in daycare centers in Mogoditshane/Thamaga Subdistrict, Botswana. Table 6. To Test Hypothesis (𝐻04) used the T-test, and ANOVA (analysis of variance) shall be used to compare three or more groups rather than just two. The analysis of variance shall be also used to compare multiple groups concurrently to find out if a relationship exists e.g., analysing the data to find out whether time factors (peak hour for injury, peak day for injury, peak season for injury) get different unintentional injuries responses in various settings.

Discussion and Conclusion disparity

The study would show whether there are differences between the characteristics of unintentional injuries and the factors contributing to such. Several studies have alluded to the findings in this study. Some of the following studies done that focused on describing the occurrence of injury. Some used descriptive designs to look at the types, prevalence, and risks of injuries in childcare centers [17,46]. A reference to this denotes that these early studies indicate that, the prevalence of unintentional injuries in childcare settings has been established in the U.S. for children aged 1-5 is 11.9 %. Children who attend childcare centers ≥10 h per week have a higher injury prevalence than those cared for by parents at home (13.9 vs. 10.4 % respectively, p < 0.05), but this differs by age [21].

A conducted a systematic review of the 26 studies reporting injury rates, 10 showed a trend toward higher childcare center injury rates in males, four studies did not find any statistical difference between boys and girls, and the remaining studies did not report injury rates based on sex. Generally, there were higher rates of injury in younger children (non- infants) compared to older children. Comparable to these findings are the results of the epidemiology study of injuries in Atlanta Daycare centers and 2-year-old children had the highest rate (2.26). Almost 47 % of injuries occurred from falls on the playground [26].

Children who attend childcare centers ≥ 10 h per week have a higher injury prevalence than those cared for by parents at home (13.9 vs. 10.4 % respectively, p < 0.05), but this differs by age [21].

Still, in yet another study that was conducted, the prevalence of UI among children aged 1–5 years was recorded as 39.1 % (259/662, 95 % CI 35.4–42.9 %) over a three-month recall. The prevalence of UI was 42.6 % (137/321) among boys and 35.8 % (122/341) among girls and this difference was not statistically significant. Proportion of children sustaining UI in the age groups 13–24; 25–36; 37–48 and 49–60 months were 33.7 % (95 % CI 27.3–40.7); 40.3 % (95 % CI 33.0–47.5); 40.9 % (95 % CI 33.5–48.6) and 43.1 % (95 % CI 35.0– 52.0) respectively.

The incidence rate of UI among the study children aged 1–5 years was 16.2 per 100 child months (95 % CI 14.6–18.1). Children in the age group of 4–5 years had a high risk of injury (43.1 %, 56/130) with an incidence rate of 17.4 (95 % CI 13.6–21.9) per 100 child months. A total of 323 UI were reported in 259 children with 207 (80 %), 42(16.2 %), and 10 (3.8 %) children experiencing one or more than two UI respectively. Among 323 UI, 306 (94.7 %) were due to falls, 9 (2.7 %) were due to burns/fire injuries and 5 (1.5 %) were due to road traffic injuries; injury type could not be determined for three injuries. Out of 306 fall injuries, 171(56 %) were among males, 135(44 %) were among females and this difference was statistically significant (P-value = 0.04). Injuries due to drowning, electrocution, or poisoning were not reported during the study period [44].

A national survey of the injury prevention activities of children’s centers to ascertain the activities they were undertaking to prevent unintentional injuries in the under-fives was carried nearly all stated that training (97 %) and assistance with planning injury prevention (94 %) would be helpful to their centers need further support if they are to effectively tackle this important public health challenge [51]. In the study Health and safety of childcare centers: An analysis of licensing specialists, reports of routine, unannounced inspections and monitored compliance with state child regulations. This was a peer periodic, routine unannounced inspection of facilities to monitor compliance with state childcare regulations [20]. Yet another study, identified a study in Minneapolis that described substantial safety concerns, specifically a lack of any fire extinguishers and fire exits, exposed electrical outlets, and in one instance, piling children in the back of a sedan using a wooden platform to create two rows of seating. Of the centers studied, 38 % were classified as marginal or poor [10]. Another study using childcare center insurance data showed climbing structures as the most hazardous, but the majority were viewed as correctable. Yet another study identified interventions that included safety policies and practices, poison prevention, passenger safety, and playground safety. Written and in person, training improved compliance with safety standards and written safety policies [26].

However, for the current study, there are no results as yet of now on the actual number of children unintentionally injured in Mogoditshane/Thamaga District daycare centers because the statistical analysis is underway. Following data analysis, recommendations for future research in this area shall be addressed.

However, for the current study, there are no results as yet of now on the actual number of children unintentionally injured in Mogoditshane/Thamaga District daycare centers because the statistical analysis is underway. Following data analysis, recommendations for future research in this area shall be addressed.

Conclusion

This study may lead to the conclusion that unintentional injuries that occur to children in daycare centers have a significant role to play in policy and injury prevention development. Factors would include context-specific risk, safety attitudes, and behavior factors needed to inform the development of effective interventions.

Furthermore, these are all significant factors results that need to be further explored in future studies.

The current study has a chance to be limited to a few cause and effect relationships between independent and dependent variables such as falls from playground equipment which result in unintentional injuries in childcare centers on falls while there are numerous factors occurring and interacting that may result in unintentional injuries for example Individual behaviors, such as falls and collisions with objects or the behavior of another child, such as pushing or hitting Environmental factors that contributed to the injury occurrence, such as a wet or slippery floor, faulty equipment or furniture, a sharp object, or a window or door, premises health records such as buildings status, emergency preparedness, rules on eating and drinking, personal hygiene and food safety/food handling.

Other factors at the childcare center would include the center’s policies on supervision and playground equipment, the child’s physical growth and cognitive understanding and age, and many other aspects that can be scrutinized to result in unintentional injuries.

Recommendations

- Because most injuries occur during free play, on the playground, and before meals, improved child supervision may help prevent injuries in preschool-aged children.

- Establish priorities from different unintentional injury factors identified in childcare settings in Mogoditshane/Thamaga Subdistrict in Botswana.

- Stimulate further research, to indicate the deficiencies in the model being used. It could lead to the model being redesigned, to make it more user-friendly in Botswana.

- Plan workshop programs leading to improved quality in reduction of unintentional injuries in childcare settings by improving the competencies of workers and ultimately the quality of promotion of prevention of unintentional injuries management in childcare settings

- Reinforce monitoring and evaluation to identify best practices for the prevention of unintentional injuries in childcare settings.

- Other potentially useful interventions to reduce child factors that contribute to injuries may be to reduce the number of children on the playground at one time and provide more structured small- group activities.

- In-service workshops for teachers and service providers would heighten their awareness of the consequences of unintentional injuries, emphasize the importance of identifying children who sustain frequent minor injuries and inform teachers of what they can do to decrease injuries at their center.

Future research

How much have the unintentional injuries strategies that have been put in place in Mogoditshane/Thamaga District day care centers achieved the aim and objectives of decreasing unintentional injury rates to their lowest conceivable levels?

There is a need for research about unintentional injuries in childcare centers that precisely looks at or accepts the relationships among numerous factors occurring and interacting that may result in unintentional injuries, cognitive, developmental, environmental factors, and the larger environmental/ecological context surrounding these factors.

Acknowledgments

I acknowledge the 52 daycare centers (respondents) who participated in this study for their time and endurance.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Retrieved from https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/fact- sheets/46-flsa-daycare.

- Retrieved from https://philosophy-question.com › library › lecture.

- Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net › publication.

- Retrieved from http://www.africanchildforum.org/clr/policy%20per%20country/ botswana/botswana_earlychildhood_2001_en.pdf.

- 1991 population census.

- (2021, November 30). Retrieved from https://www.enago.com/academy/how-to-develop-a-good- research-hypothesis/.

- (2021, November 30). Retrieved from https://opentextbc.ca/introstatopenstax/chapter/null-and- alternative-hypotheses/.

- 2022 population housing census.

- Alkhamis KN, Abdulkader RS (2020) Assessment of unintentional childhood injuries and associated factors in the pediatric clinics of a tertiary care hospital in Riyadh. Saudi Arabia. Journal Family. 27(3): 168-177.

- Alkon A, Genevro JL, Kaiser PJ, Tschann JM, Chesney M, et al. (1994) Injuries in Child Care Centers:Rates,Severity,and etiology. Pediatrics. 94(6 Pt 2): 1043-1046.

- Blakie N (2000) Designing Social Research: The Logic of Anticipation. Geneva: Polity.

- Bose K (2008) Gaps and remedies of early childhood care and education (ECCE) programs of Botswana. Educational Research and Reviews. 3: 77-82.

- Botswana Government. (2001) Botswana early childhood care and education policy. Gaborone: Government Printer.

- Brink PJ, Wood MJ (1998) Experimental Designs in advanced Design in nursing research. CA: SAGE PUBLICATIONS, Inc.

- Brussoni M, Olsen LL, Pike I, Sleet DA (2012) Risky play and children,s safety: Balncing priorities for optimal child development. International of Environmental Research. 9(9):3134-3148.

- Borse N, Sleet DA (2009) CDC Childhood Injury Report. Patterns of unintentional injuries among 0-19 year olds in the United States, 2000-2006. Fam Community Health. 32(2): 189.

- Chang A, Lugg M, Nebedum M (1989) Injuries among preschool children enrolled in day care centers. Pediatrics. 83(2): 272-7.

- Child care aware. (2017).

- Creswell JW, Creswell JD (2018) Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative,and mixed methods Approaches. SAGE Publications.

- Crowley AA, Jeon S, Rosenthal MS (2013) Health and safety of child care centers: an analysis of licensing specialist"reports of routine,unannounced inspections. AM J Public Health. 103(10): e52-8.

- Davis CS, Godfrey SE, Rankin KM (2013) Unintentional injury in early childhood:its relationship with childcare settingand provider. Martenal and child health journal. 17(9): 1541-9.

- De Vos, A. S., Strydom, H., Fouche, C. B., & Delport, CSL (1998). Research at grass roots. Pretoria: Van Schaick.

- Declaration UN (2000) Fourth millenium development goal. United Nations.

- Gong1 Hairong, Guoping Lu, Jian Ma1, Jicui Zheng, Fei Hu1, Jing Liu1, Jun Song, Shenjie Hu1, Libo Sun1, Yang Chen1, Li Xie, Xiaobo Zhang, Leilei Duan and Hong Xu (2021) Ca and its implications for prevention public healthuses and characteristics of children unintentional injuries in Emergency Department. Public Health.

- Haber and LoBiondo-Wood . (1998) Nursing research: methods and critical appraisal for evidence-based practice. Elsvier: Health sciences.

- Hashikawa AN, Newton MF, Cunningham RM, Stevens MW (2015) Unintentional injuries in child care centers in the United States: A systematic review. J Child Health Care. 19(1): 93-105.

- Hoffnung, M., Hoffnung, R. J., Seifert, K. L., Burton Smith, R., & Hine, A. (2010;2019). Childhood. Milton, Australia: John Wiley and sons.

- https://health.ri.gov/injury/. (n.d.). Unitentional injuries. Rhode Island department.

- Hyder AA, Peden M, Krug E (2009) Child health must include injury prevention. Lancet. 373(9658): 102-3.

- Konradson, P. F. (n.d). Most researchers agree that combining quantitative and qualitative techniques (sometimes called “mixed method” research) produces a richer and more comprehensive understanding of a research area. Better thesis online support.

- Lee EJ, Bass C (1990) Survey of accidents in a university day care center. J Pediatr Health Care. 4(1): 18-23.

- Macarthur C, Hu X, Wesson DE, Parkin PC (2000) Risk factors for severe injuries associated with falls from playground equipment. Analysis and prevention. 32(3): 377-82.

- Mick M, Jeffrey S, Susan H, Donna T (2010) The impact attenuation of performance of materials used under indoor play ground equipment at day care centers. Injury control and safety Promotion. 8(1): 45-47.

- Maundeni T (2013) Early Childhood Care and Education in Botswana: A Necessity That Is Accessible to Few Children. Creative education. 4(7): 54-59.

- Maunganidze L, Tsamaase M (2014) Early childhood education in Botswana: A case of fragmented "fits". International Education studies. 7: 5.

- Ruiz-Casares M (2009) Unintentional Childhood injuries in Sub- Saharan Africa: An overview of risk and protective factors. Journal of Health care for the poor and undeserved. 20(4 Suppl): 51-67.

- Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Map- of-Africa-showing-the-districts-in-Botswana_fig1_267553482.

- Navarra I. The Montessori Approach to Early Childhood Education: Benefits and Challenges of Mixed-Age Classrooms as an Essential Montessori Schools Feature. International Conference:The future of education.

- Otaala N, Njenga A, Monau R. (1989) An evaluation of the day care centers Programme in Botswana. Gaborone: UNICEF.

- Petridou E, Sibert J, Dedoukou X, Skalkidis I, Trichopoulos D (2002) Injuries in public and private playgrounds: The relative contribution of structural,equipment and human factors. Acta Paediatrics. 91(6): 691-7.

- Polit DF, Hungler BP (1999) Nursing research: principles and methods. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott company.

- Sade RM (2003) Publication of unethical research studies: the importance of informed consent. Annals of Thoracic surgery. 75(2): 325-328.

- Saunders M, Lewis P, Thornhill A (2012) Research methods for business studies. Pearson Education Ltd., Harlow.

- Sharma SL, Reddy NS, Ramanujam K, Jennifer MS, Gunasekaran A, et al. (2018) Unintentional injuries among children aged 1-5 years:understanding the burden,risk factors and severity in urban slums of southern India. Injury Epidemiology. 5(1): 41.

- Singh, S. (2018). Sampling. Kuala Lumpar.

- Sacks JJ, Smith JD, Kaplan KM, Lambert DA, Sattin RW, et al. (1989) The epidemiology of J injuries in Atlanta day care centers. JAMA. 262(12): 1641-5.

- Sorensen HT, Sabroe S, Olsen J (1996) A framwork for evaluation of secondary data sources for epidemiological research. International Journal of Epidemiology. 25(2): 435-442.

- Srinivasan & Lohith. (2017) "Pilot Study" -Assessment of validity and reliability" . India Studies in Business and economics, strategic Marketing, 43-49.

- Toh TH, Lee JJML, Wong CK (2006) Playground injuries in Singaporean children with special reference to falls from monkey- bars.

- UNICEF. (2019).

- Watson MC, Mulvaney CA, Kendrick D, Stewart J, Coupland C, et al. (2014) The national survey of the injury prevention activities of children,s centers. Health Soc Care Community. 22(1): 40-46.

- Yamane T (1967) Statistics’, an introductory analysis. New York: Harper & Row.

- Bianca ZS, Carla M, Rausch P, Cristina PRK, Lucia BV (2014) Uintentional injuries in Brazilian preschool children. Pesq Brass Odontoped Clin Interg. 14(1): 35-41.

- Tinsworth D, McDonald J (2001) Tinsworth DK, McDonald JE (2001) Special Study: Injuries and Deaths Associated with Children’s Playground Equipment. Washington (DC): U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission.

- Phelan KJ, Khoury J, Kalkwarf HJ, Lanphear BP (2001) Phelan KJ, Khoury J, Kalkwarf HJ, Lanphear BP (2001)Trends and patterns of playground injuries in United States children and adolescents. Ambulatory Pediatrics. 1(4): 227-33.